PFO – Patent Foramen Ovale and DCS Risk in Diving

Scuba diving is an exhilarating adventure that allows us to explore the mesmerizing underwater world. However, it’s crucial to be aware of potential health risks associated with this activity. One such risk that has gained attention among divers is the presence of Patent Foramen Ovale (PFO) and its connection to Decompression Sickness (DCS).

In this article, I will explain what you need to know about PFO, its prevalence, how it affects DCS risk, and what it means for you as a diver.

Understanding Patent Foramen Ovale

What is Patent Foramen Oval?

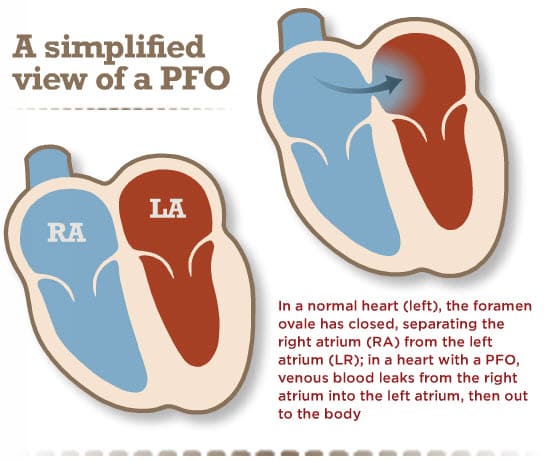

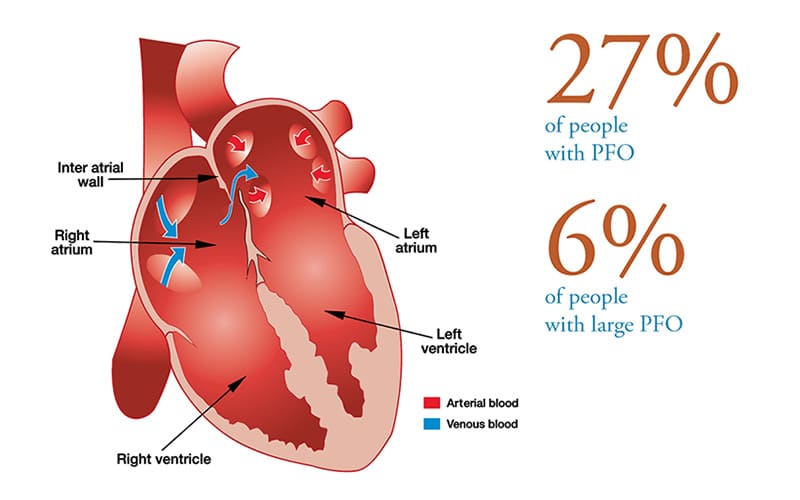

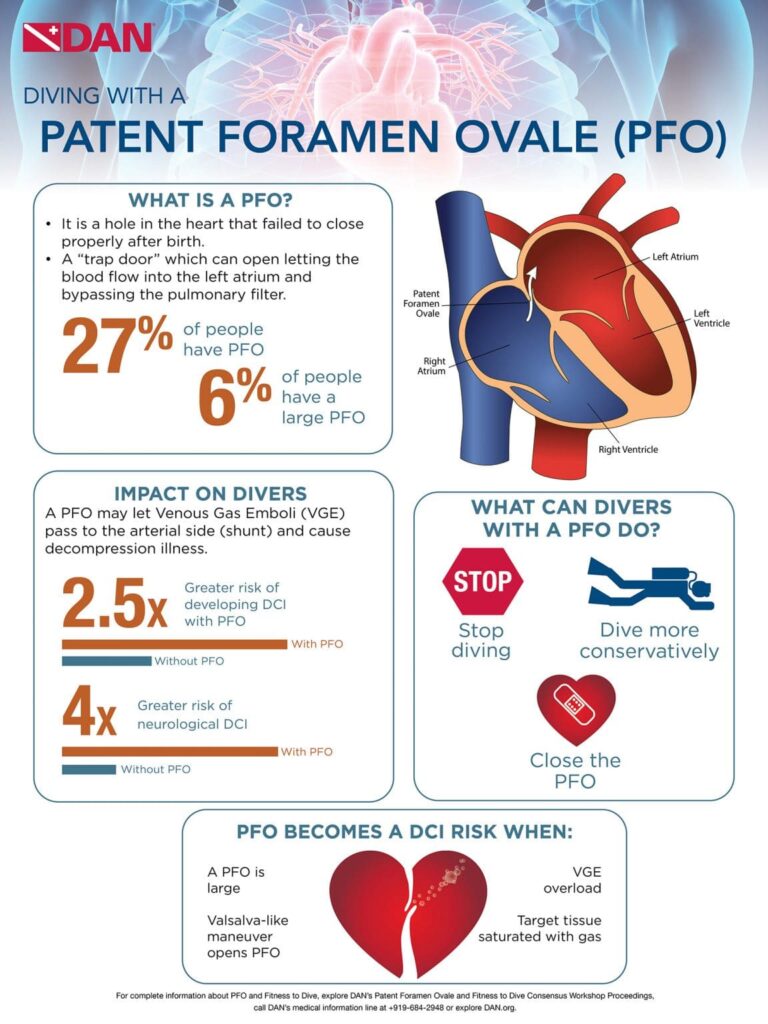

Patent Foramen Ovale is a condition where a small opening in the atrial septum, which exists in the fetal heart, fails to close after birth.

This opening, called the foramen ovale, normally allows blood to bypass the fetal lungs but closes soon after birth.

However, in some individuals, it remains open, allowing a tiny amount of blood to shunt from the right atrium to the left atrium.

- PFO is a condition where a small opening in the atrial septum, which exists in the fetal heart, fails to close after birth.

- Normally, this opening closes soon after birth.

- In some individuals it remains open, allowing a tiny amount of blood to shunt from the right atrium to the left atrium.

How PFO Increases DCS Risk

DCS – The Formation of Bubbles

Bubbles form during and after scuba diving ascents, similar to the bubbles in a carbonated beverage. Decompression sickness occurs when these bubbles produce symptoms. Even after normal decompression, “silent” micro-bubbles can form in venous blood.

- Bubbles form during and after scuba diving ascents, similar to the bubbles in a carbonated beverage.

- Decompression sickness occurs when these bubbles produce symptoms.

- Even after normal decompression, “silent” micro-bubbles can form in venous blood.

The Role of Patent Foramen Ovale in DCS

Venous bubbles may be shunted through a PFO when they reach the right atrium. These bubbles can become arterialized, potentially causing symptoms if they lodge in the arterial supply to tissues.

There isn’t a direct correlation between Patent Foramen Ovale and DCS, so the specific relationship remains unclear. It’s important to note that intrapulmonary shunts are common in most individuals, further complicating the connection between PFO and DCS.

- Venous bubbles may be shunted through a PFO when they reach the right atrium.

- These bubbles can become arterialized, potentially causing symptoms if they lodge in the arterial supply to tissues.

PFO Increases Overall DCS Risk

- Divers with PFO face a 2.5 times higher risk of DCS compared to those without a PFO.

- Specifically, they are four times more likely to experience neurological DCS, which affects the nervous system.

- However, it’s crucial to note that the absolute incidence of neurological DCS in divers with PFO is estimated at 4.7 cases per 10,000 dives.

Link Between PFO and Spinal DCI

- Studies have shown a significant correlation between Patent Foramen Ovale and spinal DCS.

- The prevalence of large PFO in divers with spinal DCS is approximately 44 percent

- It is it’s only 14.2 percent in divers without PFO.

- Half of the divers with Patent Foramen Ovale-related DCI have a PFO with a diameter of one centimeter or larger,

- This indicates that the greatest risk of DCI lies with those having the largest PFOs.

- Approximately 6% of divers have a large PFO.

Types of DCS Associated with Patent Foramen Ovale

- PFO has been linked to various forms of DCS, including;

- Cerebral (affecting the brain)

- Cutaneous DCS (skin bends)

- Spinal (affecting the spinal cord)

- Inner-ear DCS (IEDCS)

- The strongest association exists between PFO and cutaneous and inner-ear DCS.

- Approximately 74% of cases of inner-ear DCS present with isolated inner-ear symptoms.

- 80 percent of these cases have a large, spontaneously shunting PFO.

Do You Have a PFO?

When divers learn about PFO, the first question they usually ask is whether they have one.

PFO Is Typically Asymptomatic

Patent Foramen Ovale itself is usually asymptomatic. It has been associated with migraine with aura and cryptogenic stroke, but the evidence is conflicting.

- PFOs vary in size, ranging from 1 to 19 millimeters (0.04 to 0.75 inches).

- They tend to be larger in older adults, possibly due to elevated right heart pressures as people age.

- This can reduce the pressure difference between the left and right atrium, allowing PFOs to expand.

The Prevalence of PFO

- PFO remains open, or patent, in about 25 to 34% of adults, with detectable shunting occurring in 8 to 10%.

- Research conducted at the Mayo Clinic revealed that PFO prevalence is higher in younger individuals but levels off at around 27% in the general population.

- There are no significant differences in Patent Foramen Ovale prevalence between males and females in various age groups.

- Decompression sickness in divers is relatively rare:

- DCS incidence ranges from 0.01% to 0.095%.

- Among divers with a known Patent Foramen Ovale, DCS incidence ranges from 0.5% to 1.8%.

Should I Get Tested for a PFO?

- Routine screening for PFO in divers is not recommended.

- Non-cutaneous manifestations of “mild DCS” or joint pain only DCS are not indications for PFO investigation.

- Screening is reasonable for high-risk individuals, such as those with migraines, congenital heart disease, or a family history of PFO.

- Echocardiography with bubble contrast is the standard method for detection.

The Importance of Proper PFO Testing

- It is crucial to seek medical centers experienced in PFO testing.

- To accurately detect PFO, the testing must include bubble contrast, ideally combined with a trans-thoracic echocardiogram (TTE).

- Two-dimensional and color-flow echocardiography without bubble contrast won’t provide adequate results.

- Provocation maneuvers are an essential part of the testing process.

- These maneuvers, such as the Valsalva release or sniffing, help promote the identification of right-to-left shunt.

- They are performed when the right atrium is densely filled with bubble contrast.

What Does a Positive PFO Test Mean?

- A positive PFO test can have different implications based on the circumstances.

- If a spontaneous shunt is detected without provocation or if a large, provoked shunt occurs after a dive when venous gas emboli are present, it is considered a risk factor for certain forms of DCS.

- These forms may involve cerebral, spinal, vestibulocochlear, or cutaneous manifestations.

- Smaller shunts also exist but are associated with a lower and less defined risk of DCS.

- The significance of these minor shunts should be interpreted within the clinical context that led to the testing.

It’s essential to note that detecting a Patent Foramen Ovale after experiencing DCS does not automatically imply that the PFO caused the condition. The relationship between PFO and DCS is complex and not always straightforward.

Understanding Positive PFO Test Results

The Decision-Making Process

- When a diver receives a positive PFO diagnosis that is likely associated with an increased risk of DCS, several options become available.

- It’s crucial to make informed decisions in consultation with a diving physician who specializes in diving medicine.

Your Options If Diagnosed With PFO

You have three options if diagnosed with Patent Foramen Ovale; stop diving, dive more conservatively, or have the PFO surgically closed.

1st Option: Stop Diving

- For some divers, the best choice might be to temporarily or permanently stop diving.

- This decision depends on individual circumstances and the severity of the condition.

- Safety should always come first.

2nd Option: Dive More Conservatively

- Another approach is to modify your diving practices to reduce the risk of significant venous bubble formation and subsequent right-to-left shunting of these bubbles across a PFO.

- Here are some strategies that may help:

- Reducing Dive Times: Stay well within accepted no-stop limits to minimize the risk of DCS.

- Limiting Dives: Consider doing only one dive per day to reduce the overall exposure.

- Nitrox Use: Utilize nitrox with air dive planning tools to lower the risk.

- Safety Stops: Extend your safety stop or decompression time at shallow stops.

- Post-Dive Activities: Avoid heavy exercise, lifting, or straining for at least three hours after diving.

- These strategies should be discussed with a diving medicine expert and tailored to your specific situation.

- Opting for very conservative diving may be an option for recreational divers who only dive infrequently.

3rd Option: Close the PFO

- Closing the PFO is another option to consider, but it’s crucial to understand that this does not guarantee freedom from DCS in the future.

- Percutaneous closure (a less-invasive surgical procedure) is not without risk and should be weighed against the individual’s DCS risk.

- This decision involves weighing the potential risks and benefits, considering your clinical history, and consulting with a medical expert experienced in diving medicine.

- Patent Foramen Ovale closure may be suitable for dive professionals, technical divers, and recreational divers who are very active in diving.

How is a PFO Closed?

Fixing a Patent Foramen Ovale involves percutaneous closure; a minimally invasive surgery on the heart, via a needle through the femoral vein in the thigh.

- Firstly, imaging is done using a combination of fluoroscopy and ultrasound, either TEE or intracardiac echo.

- Secondly, a device, such as the Amplatzer PFO Occluder, is inserted to close the defect.

- It’s deployed through a small catheter across the PFO.

- The entire procedure takes about an hour, typically allowing patients to go home the same day or the following morning.

Diving After PFO Closure

Divers who have undergone PFO closure may return to diving after clearance by a cardiologist and a diving medicine specialist. Evidence suggests that closure may decrease DCS risk in divers with a history of DCS.

A positive PFO test result doesn’t mean the end of your diving adventures, but it does require thoughtful consideration of your options.

Diving Risk Factors for DCS with PFO

DCS risk is highest in dive profiles that evoke silent venous gas emboli. This risk increases if you’ve experienced multiple episodes of DCS.

- DCS risk is highest in dive profiles that evoke silent venous gas emboli (microbubbles)

- This risk is higher if you have had DCS previously.

Notable Dive Risk Factors With PFO

- Long, deep dives

- Aggressive decompression protocols

- Omitted decompression

- Rapid ascent

- Heavy work at depth

- Cold on decompression

- Repetitive dives over multiple days

Caution for Divers with PFO

- Divers who have experienced unexplained neurological DCS, inner ear DCS, or skin bends (cutis marmorata) and are found to have PFO should be cautious about returning to diving.

- Clearance to dive should be based on the judgment of a trained practitioner.

Keep Patent Foramen Ovale In Mind If You Experience DCS Symptoms

In conclusion, as a scuba diver, it’s essential to be informed about the potential risks associated with PFO and its connection to Decompression Sickness.

While PFO is not a guaranteed ticket to DCS, it’s crucial to consider individual factors and seek expert advice when making decisions about diving with PFO or undergoing closure procedures.

Your safety and well-being underwater should always be a top priority.

PFO References

DAN Guidelines for Patent Foramen Ovale and Diving

Can I dive with a PFO? Diving Diseases Research Center (DDRC)

Everything You Wanted To Know About PFOs and Decompression Illness, But Were Too Busy Decompressing to Ask, by Doug Ebersole M.D. InDepth Magazine, Mar 2021

Patent Foramen Ovale in Diving. Eric J. Hexdall; Jeffrey S. Cooper. StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan.

Increased Risk of Decompression Sickness When Diving With a Right-to-Left Shunt: Results of a Prospective Single-Blinded Observational Study (The “Carotid Doppler” Study). Germonpré et al. Front. Physiol., 29 October 2021 Sec. Environmental, Aviation and Space Physiology Volume 12 – 2021

About The Author

Andy Davis is a RAID, PADI TecRec, ANDI, BSAC, and SSI-qualified independent technical diving instructor who specializes in teaching sidemount, trimix, and advanced wreck diving courses.

Currently residing in Subic Bay, Philippines; he has amassed more than 10,000 open-circuit and CCR dives over three decades of challenging diving across the globe.

Andy has published numerous diving magazine articles and designed advanced certification courses for several dive training agencies, He regularly tests and reviews new dive gear for scuba equipment manufacturers. Andy is currently writing a series of advanced diving books and creating a range of tech diving clothing and accessories.

Prior to becoming a professional technical diving educator in 2006, Andy was a commissioned officer in the Royal Air Force and has served in Iraq, Afghanistan, Belize, and Cyprus.

In 2023, Andy was named in the “Who’s Who of Sidemount” list by GUE InDepth Magazine.

Purchase my exclusive diving ebooks!

Originally posted 2023-09-15 16:46:28.