The Importance of Deep Stops: Rethinking Ascent Patterns From Decompression Dives

An abridged version of this deep stops article was originally in DeepTech, 5:64; and the full version was subsequently published in Cave Diving Group Newsletter, 121:2-5.

by Richard L. Pyle

Before I begin, let’s make something perfectly clear: I am a fish-nerd (i.e., an ichthyologist). For the purposes of this commentary, that means two things. First, it means that I have spent a lot of time underwater. Second, although I am I biologist and understand quite a bit about animal physiology, I am not an expert in decompression physiology. Keep these two things in mind when you read what I have to say.

Back before the concept of “technical diving” existed, I used to do more dives to depths of 180-220 feet than I care to remember. Because of the tremendous sample size of dives, I eventually began to notice a few patterns. Quite frequently after these dives, I would feel some level of fatigue or malaise. It was clear that these post-dive symptoms had more to do with inert-gas loading than with physical exertion or thermal exposure, because the symptoms would generally be much more severe after spending less than an hour in the water for a 200-foot dive than they would after spending 4 to 6 hours at much shallower depths.

The interesting thing was that these symptoms were not terribly consistent. Sometimes I hardly felt any symptoms at all. At other times I would be so sleepy after a dive that I would find it difficult to stay awake on the drive home. I tried to correlate the severity of symptoms with a wide variety of factors, such as the magnitude of the exposure, the amount of extra time I spent on the 10-foot decompression stop, the strength of the current, the clarity of the water, water temperature, how much sleep I had the night before, level of dehydration…you name it…but none of these obvious factors seemed to have anything to do with it.

A practice reducing post-dive fatigue

Finally I figured out what it was – fish! Yup, that’s right…on dives when I collected fish, I had hardly any post-dive fatigue. On dives when I did not catch anything, the symptoms would tend to be quite strong. I was actually quite amazed by how consistent this correlation was.

The problem, though, was that it didn’t make any sense. Why would these symptoms have anything to do with catching fish? In fact, I would expect more severe symptoms after fish-collecting dives because my level of exertion while on the bottom during those dives tended to be greater (chasing fish isn’t always easy).

There was one other difference, though. You see, most fishes have a gas-filled internal organ called a “swimbladder” – basically a fish buoyancy compensator. If a fish is brought straight to the surface from 200 feet, its swimbladder would expand to about seven times its original size and crush the other organs.

Because I generally wanted to keep the fishes I collected alive, I would need to stop at some point during the ascent and temporarily insert a hypodermic needle into their swimbladders, venting off the excess gas. Typically, the depth at which I needed to do this was much deeper than my first required decompression stop.

Non-deliberate deep stops

For example, on an average 200-foot dive, my first decompression stop would usually be somewhere in the neighborhood of 50 feet, but the depth I needed to stop for the fish would be around 125 feet. So, whenever I collected fish, my ascent profile would include an extra 2-3 minute stop much deeper than my first “required” decompression stop. Unfortunately, this didn’t make any sense either.

When you think only in terms of dissolved gas tensions in blood and tissues (as virtually all decompression algorithms in use today do), you would expect more decompression problems with the included deep stops because more time is spent at a greater depth.

As someone who tends to have more faith in what actually happens in the real world than what should happen according to the theoretical world, I decided to start including the deep stops on all of my decompression dives, whether or not I collected fish. Guess what?

My symptoms of fatigue virtually disappeared altogether! It was nothing short of amazing! I mean I actually started getting some work done during the afternoons and evenings of days when I did a morning deep dive. I started telling people about my amazing discovery, but was invariably met with skepticism, and sometimes stern lectures from “experts” about how this must be wrong.

“Obviously,” they would tell me, “you should get out of deep water as quickly as possible to minimize additional gas loading.” Not being a person who enjoys confrontation, I kept quiet about my practice of including these “deep decompression stops”.

Observed benefit from deep stops

As the years passed, I became more and more convinced of the value of these deep stops for reducing the probability of decompression sickness (DCS). In all cases where I had some sort of post-dive symptoms, ranging from fatigue to shoulder pain to quadriplegia in one case, it was on a dive where I omitted the deep decompression stops.

As a scientist by profession, I feel a need to understand mechanisms underlying observed phenomena. Consequently, I was always bothered by the apparent paradox of my decompression profiles. Then I saw a presentation by Dr. David Yount at the 1989 meeting of the American Academy of Underwater Sciences (AAUS). For those of you who don’t know who he is, Dr. Yount is a professor of physics at the University of Hawaii, and one of the creators of the “Varying-Permeability Model” (VPM) of decompression calculation.

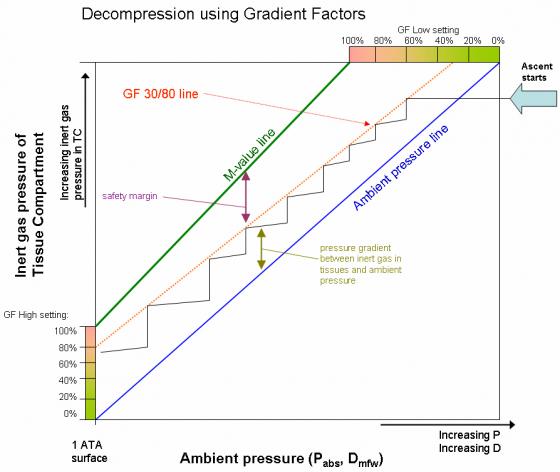

This model takes into account the presence of “micronuclei” (gas-phase bubbles in blood and tissues) and factors that cause these bubbles to grow or shrink during decompression. The upshot is that the VPM calls for initial decompression stops that are much deeper than those suggested by neo-Haldanian (i.e., “compartment-based”) decompression models. It finally started to make sense to me. (For a good overview of the VPM, read Chapter 6 of Best Publishing’s Hyperbaric Medicine and Physiology; Yount, 1988.)

Since you already know I am not an expert in diving physiology, let me explain what I believe is going on in terms that educated divers should be able to understand.

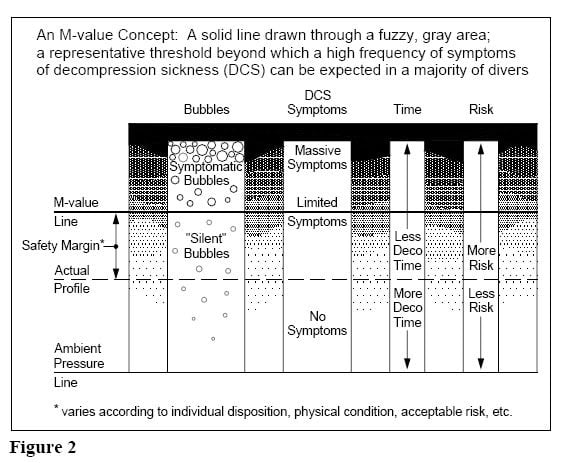

First, most readers should be aware that intravascular bubbles are routinely detected after the majority of dives – even “no decompression” dives. The bubbles are there – they just don’t always lead to DCS symptoms.

Now; most deep decompression dives conducted by “technical” divers (as opposed to commercial or military divers) are very-much sub- saturation dives. In other words, they have relatively short bottom-times (I would consider 2 hours at 300 feet a “short” bottom time in this context).

Depending on the depth and duration of the dive, and the mixtures used, there is usually a relatively long ascent “stretch” (or “pull”) between the bottom and the first decompression stop as calculated by any theoretical compartment-based model. The shorter the bottom time, the greater this ascent stretch is. Conventional mentality holds that you should “get the hell out of deep water” as quickly as possible to minimize additional gas loading. Many people even believe that you should use faster ascent rates during the deeper portions of the ascent. The point is, divers are routinely making ascents with relatively dramatic drops in ambient pressure in relatively short periods of time – just so they can “get the hell out of deep water”.

This, I believe, is where the problem is. Maybe it has to do with the time required for blood to pass all the way through a typical diver’s circulatory system. Perhaps it has to do with tiny bubbles being formed as blood passes through valves in the heart, and growing large due to gas diffusion from the surrounding blood.

Whatever the physiological basis, I believe that bubbles are being formed and/or are encouraged to grow in size during the initial non-stop ascent from depth. I’ve learned a lot about bubble physics over the last year, more than I want to relate here – I’ll leave that for someone who really understands the subject.

For now, suffice it to say that whether or not a bubble will shrink or grow depends on many complex factors, including the size of the bubble at any given moment.

Smaller bubbles are more apt to shrink during decompression; larger bubbles are more apt to grow and possibly lead to DCS. Thus, to minimize the probability of DCS, it is important to keep the size of the bubbles small.

Relatively rapid ascents from deep water to the first required decompression stop do not help to keep bubbles small! By slowing the initial ascent to the first decompression stop, (e.g., by the inclusion of one or more deep decompression stops), perhaps the bubbles are kept small enough that they continue to shrink during the remainder of the decompression stops.

If there is any truth to this, I suspect that the enormous variability in incidence of DCS has more to do with the pattern of ascent from the bottom to the first decompression stop, than it has to do with the remainder of the decompression profile.

DCS is an extraordinarily complex phenomenon – more complex than even the most advanced diving physiologists have been able to elucidate. The unfortunate thing is that we will likely never understand it entirely, largely because our bodies are incredibly chaotic environments, and that level of chaos will hinder any attempts to make predictions about how to avoid DCS. But I think that we, as sub-saturation decompression divers, can significantly reduce the probability of getting bent if we alter the way we make our initial ascent from depth.

Some of you may now be thinking “But he said he’s not an expert in diving physiology – why should I believe him?” If you are thinking this, then good – that’s exactly what I want you to think because you shouldn’t trust just me.

So, why don’t you dig up your September ’95 issue of DeepTech (Issue 3) and read Bruce Weinke’s article? I know it covers some pretty sophisticated stuff, but you should keep re- reading it until you do understand it.

Why don’t you call up aquaCorps and order audio tape number 9 (“Bubble Decompression Strategies”) from the tek.95 conference, and listen to Eric Maiken explain a few things about gas physics that you probably didn’t know before.

While you’re at it, why don’t you order the audio tape from the “Understanding Trimix Tables” session at the recent tek.96 conference? You can listen to Andre Galerne (arguably the “father of trimix”) talk about how the incidence of DCS was reduced dramatically when they included an extra deep decompression stop over and above what was required by the tables. On the same tape you can listen to Jean-Pierre Imbert of COMEX (the French commercial diving operation which conducts some of the world’s deepest dives) talk about a whole new way of looking at decompression profiles which includes initial stops that are much deeper than what most tables call for.

Why don’t you ask George Irvine what he meant when he said he includes “three or four short deep stops into the plan prior to using the first stop recommended by each of the [decompression] programs” in the January, ’96 issue of DeepTech (Issue 4)?

If that’s not enough, then check out Dr. Peter Bennett’s editorial in the January/February 1996 Alert Diver magazine; he’s talking about basically the same thing in the context of recreational diving.

If you really want to read an eye-opening article, see if you can find the report on the habits of diving fishermen in the Torres Strait by LeMessurier and Hills (listed in the References section at the end of this article). The lists goes on and on. The point is, I don’t seem to be the only one advocating deep decompression stops.

Are you still skeptical?

Let me ask you this: Do you believe that so-called “safety stops” after so-called “no- decompression” dives are useful in reducing probability of DCI?

If not, then you should take a look at the statistics compiled by Diver’s Alert Network.

If so, then you are already doing “deep stops” on your “no-decompression” dives.

If it makes you feel better, then call the extra deep decompression stops “deep safety stops” which you do before you ascend to your first “required” decompression stop. Think about it this way: Your first “required” decompression stop is functionally equivalent to the surface on a dive that is taken to the absolute maximum limit of the “no-decompression” bottom time. Wouldn’t you think that “safety stops” on “no-decompression” dives would be most important after a dive made all the way to the “no- decompression” limit?

Some of you may be thinking, “I already make safety stops on my decompression dives – I always stop 10 or 20 feet deeper than my first required stop.” While this is a step in the right direction, it is not what I am talking about here. “Why not?“, you ask, “I do my safety stops on no-decompression dives at 20 feet. Why shouldn’t I do my deep safety stops 20 feet below my first required ceiling?” I’ll tell you why – because the safety stops have to do with preventing bubble growth, and bubble growth is in part a function of a change in ambient pressure, not a function of linear feet.

Suppose that, after a dive to 75 feet, you make a safety stop at 20 feet. Well, the ambient pressure at sea level is 1 ATA. The ambient pressure at 75 feet is about 3.3 ATA. The ambient pressure at your 20-foot safety stop is 1.6 ATA – which represents roughly the midpoint in pressure between 3.3 ATA and 1 ATA.

Now, suppose you’re on a dive to 200 feet (about 7 ATA) and your first required decompression stop is 50 feet (about 2.5 ATA). The ambient pressure midpoint between these two depths is 4.75 ATA, or a little less than 125 feet. Thus, on this dive you would want to make your deep safety stop at about 125 feet – exactly the depth I used to stop to stick a hypodermic needle in my little fishies.

But of course, the physics and physiology are much more complex than this. It may be that ambient pressure mid- points are not the ideal depth for safety-stops – in fact, I can tell you with near certainty that they are not. From what I understand of bubble-based decompression models, initial decompression stops should be a function of absolute ambient pressure changes, rather than proportional ambient pressure changes, and thus should be even deeper than the ambient pressure mid-point for most of our decompression dives.

Unfortunately, I seriously doubt that decompression computers will begin incorporating bubble-based decompression algorithms, at least not in their complete form. Until then, we decompression divers need a simpler method – a rule of thumb to follow that doesn’t require the processing power of an electronic computer.

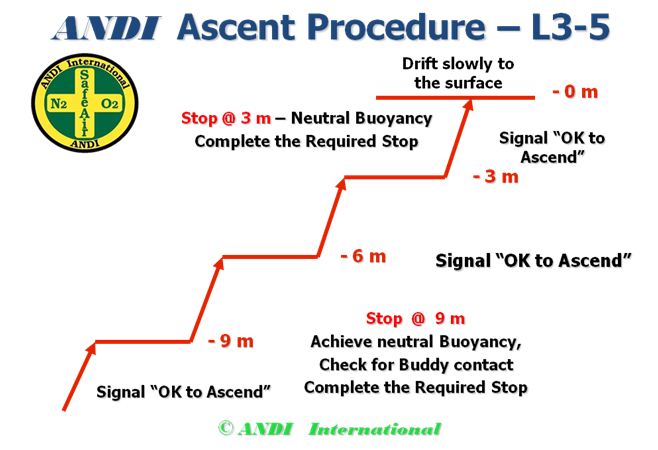

Perhaps the ideal method would be simply to slow down the ascent rate during the deep portion of the ascent. Unfortunately, this is rather difficult to do – especially in open water. Instead, I think you should include one or more discrete, short-duration stops to break up those long ascents. Whether or not it is physiologically correct, you should think of them as pit-stops to allow your body to “catch up” with the changing ambient pressure.

Pyle method for calculating deep stops

Here is my method for incorporating deep safety stops:

1) Calculate a decompression profile for the dive you wish to do, using whatever software you normally use.

2) Take the distance between the bottom portion of the dive (at the time you begin your ascent) and the first “required” decompression stop, and find the midpoint. You can use the ambient pressure midpoint if you want, but for most dives in the “technical” diving range, the linear distance midpoint will be close enough and is easier to calculate. This depth will be your first deep safety stop, and the stop should be about 2-3 minutes in duration.

3) Re-calculate the decompression profile by including the deep safety stop in the profile (most software will allow for multi-level profile calculations).

4) If the distance between your first deep safety stop and your first “required” stop is greater than 30 feet, then add a second deep safety stop at the midpoint between the first deep safety stop and the first required stop.

5) Repeat as necessary until there is less than 30 feet between your last deep safety stop and the first required safety stop.

For example, suppose you want to do a trimix dive to 300 feet, and your desktop software says that your first “required” decompression stop is 100 feet. You should recalculate the profile by adding short (2-minute) stops at 200 feet, 150 feet, and 125 feet. Of course, since your computer software assumes that you are still on-gassing during these stops, the rest of the calculated decompression time will be slightly longer than it would have been if you did not include the stops.

However, in my experience and apparently in the experience of many others, the reduction in probability of DCI will far outweigh the costs of doing the extra hang time. In fact, I’d be willing to wager that the advantages of deep safety stops are so large that you could actually reduce the total decompression time (by doing shorter shallow stops) and still have a lower probability of getting bent – but until someone can provide more evidence to support that contention, you should definitely play it safe and do the extra decompression time.

Personal responsibility for decompression diving

One final point. As anyone who reads my posts on the internet diving forums already knows, I am a strong advocate of personal responsibility in diving. If you choose to follow my suggestions and include deep safety stops on your decompression dives, then that’s swell. If you decide to continue following your computer-generated decompression profiles, that’s fine too.

But whatever you do, you are completely and entirely responsible for whatever happens to you underwater! You are a terrestrial mammal for crying out loud – you have no business going underwater in the first place. If you cannot accept the responsibility, then stay out of the water. If you get bent after a dive on which you have included deep safety stops by my suggested method, then it was your own fault for being stupid enough to listen to decompression advice from a fish nerd!

References:

Bennett, P.B. 1996. Rate of ascent revisited. Alert Diver, January/February 1996: 2.

Hamilton, B. and G. Irvine. 1996. A hard look at decompression software. DeepTech, No. 4 (January 1996): 19- 23

LeMessurier, D.H. and B.A. Hills. 1965. Decompression sickness: A thermodynamic approach arising from a study of Torres Strait diving techniques. Scientific Results of Marine Biological Research. Nr. 48: Essays in Marine Physiology, OSLO Universitetsforlaget: 54-84.

Weinke, B. 1995. The reduced gradient bubble model and phase mechanics. DeepTech, No. 3 (September 1995): 29-37.

Yount, D.E. 1988. Chapter 6. Theoretical considerations of Safe Decompression. In: Hyperbaric Medicine and Physiology (Y-C Lin and A.K.C. Niu, eds.), Best Publishing Co., San Pedro, pp. 69-97.

I would like to thank Eric Maiken for explaining bubble physics to me and for adding some theoretical foundation to my silly ideas

About The Author

Andy Davis is a RAID, PADI TecRec, ANDI, BSAC, and SSI-qualified independent technical diving instructor who specializes in teaching sidemount, trimix, and advanced wreck diving courses.

Currently residing in Subic Bay, Philippines; he has amassed more than 10,000 open-circuit and CCR dives over three decades of challenging diving across the globe.

Andy has published numerous diving magazine articles and designed advanced certification courses for several dive training agencies, He regularly tests and reviews new dive gear for scuba equipment manufacturers. Andy is currently writing a series of advanced diving books and creating a range of tech diving clothing and accessories.

Prior to becoming a professional technical diving educator in 2006, Andy was a commissioned officer in the Royal Air Force and has served in Iraq, Afghanistan, Belize, and Cyprus.

In 2023, Andy was named in the “Who’s Who of Sidemount” list by GUE InDepth Magazine.

Purchase my exclusive diving ebooks!

Originally posted 2018-03-07 23:55:17.