The History of Subic Bay

A concise history of Subic Bay, charting 500 years of turmoil, conflict and occupation

The history of Subic Bay reflects many centuries of war and turbulence. The Bay has strategic significance as a protected deep-water harbour and that has caused it to become a focus of maritime conflict for hundreds of years. Prior to becoming a major centre for tourism, scuba diving and a commercial tax-haven, the bay was occupied by Spanish, Japanese and American forces and played a pivotal role in both the Spanish-American War and World War 2.

Subic Bay: Origins of the Name

The name “Subic” has evolved over the history of Subic Bay, influenced by the varied populations that have governed the area. It was derived from the native word “hubek”, which means “head of a plow”. That name has persisted, although the spelling and pronunciation have changed over the ages – as Spanish colonists interpreted it as “Subiq”, followed by early American influence changing it to “Subig” and finally, its modern pronunciation “Subic.

Subic Bay History: Spanish Colonization

In 1542, a Spanish conquistador and explorer named Juan de Salcedo, first visited the bay and recognized its potential as a fine shelter for shipping. The area did not, however, become an operational harbour until over 350 years later.Although the Spanish fleet did transfer temporarily from Manila Bay to Subic during the British occupation of Manila (1762-1764), Subic was not actually developed as a port and harbour until the mid-1800’s. The Spanish fleet was originally established in Cavite, Manila – but this location increasingly suffered from sickness and presented strategic vulnerabilities to the fleet due to lack of shelter from storms and enemy fleets.

Barretto Beach

Following a military survey conducted in 1868, Spanish King Alfonso II issued a royal decree in 1884, that declared Subic as “a naval port and the property appertaining thereto set aside for naval purposes.” The construction of the ‘Arsenal en Olongapo‘ – an arsenal and ship repair yard was authorized on March 8, 1885, with construction work commencing the following September.

Using local Filipino labor (working in lieu of tax payments) the Spanish dredged the harbour basin and built a drainage canal surrounding the port – making the Navy yard into an “island”. This canal reduced disease by draining the swampy terrain and also served as a defensive barrier around the base. The canal still exists, surrounding the SBMA/SBFZ area, crossed by bridges into Olongapo town.

Several sea-walls, causeways and a railway line were constructed over the tidal flats bordering the shipyard. These required quarrying thousands of tons of dirt and rock from the Kalalake area of Olongapo. That former quarry now forms the lagoon at Bicentennial Park in SBMA.

When the Arsenal was finished, the gunboats Caviteño, the Santa Ana, and the San Quentin were assigned to its defense. These were complemented by gun batteries on the station and on Grande Island, in the mouth of the Bay.

History of Subic Bay: American Rule (1898 – 1941)

The Spanish-American War commenced on 25 April 1898, when Commodore George Dewey, Commander of the U.S. Asiatic Fleet, received word that war with Spain had been declared and sailed from Hong Kong to attack the Spanish fleet in Manila Bay.

In response, the Spanish naval commander, Rear Admiral Patricio Montojo, moved the majority of his fleet to Subic Bay, which was considered to be a more defensible position than Cavite and would allow his fleet to conduct a strategic ambush on the rear of the American fleet when they entered Manila Bay. Spanish preparations at Subic Bay included the scuttling of the San Quentin and two other vessels to limit access into harbor. However, other critical preparations were not completed – and the Spanish failed to install their four 6″ guns on Grande Island, whilst only laying 4 out of 15 available mines that they possessed into the mouth of the Bay.

These delayed preparations, along with (accurate) suspicions that the Americans had been given intelligence about the movements of the Spanish Fleet caused Montojo to reverse his decision and return his fleet to Manila Bay.

At dawn, on the 1st of May 1898, the American fleet entered Manila Bay, closing to within 5,000 yards of the Spanish fleet before opening fire. The Spanish Fleet was totally annihilated, with 167 men killed and 214 wounded. In contrast, the American Fleet suffered no fatalities.

During the Philippine – American War, Filipino forces established control of the port and naval base, but were ejected by military action during the summer and autumn of 1899. The American flag was finally raised over Olongapo in December that year, when the U.S. Marines took over operational and administrative control of Olongapo town.

Subic Bay was not occupied by the American military until 1902, due to disagreements over the best strategic location for fleet base. In 1900, the General Board of the United States Navy had recommended Guimaras Island, south of Manila, as the most suitable site for the main American naval base in the Philippines. However, George Dewey, Admiral of the Navy, and Admiral George C. Remey, Commander of the Asiatic Fleet, disagreed and insisted upon the strategic benefits of Subic Bay. Dewey and Remey were successful in their argument – and Subic was chosen.

Supporting that decision, President Theodore Roosevelt stated:

“If we are to exert the slightest influence in Western Asia, it is of the highest importance that we have a naval station in Subic Bay.”

Consequently, the U.S. Congress appropriated funds totaling $1 million ($27040000 in 2011 dollars) for the development of a major naval facility in Subic Bay.

However, in 1907, escalating tensions with Japan caused a shift in policy – where more strategic emphasis was placed upon the development of a major base at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. Consequently, all major work to further develop the facility in Subic Bay was ceased. Despite further construction, the facilities at Subic Bay were heavily involved in overhauling and maintaining the U.S. fleet during World War I.

By the mid-1940’s, war with Japan was imminent and the American military took measures to prevent the Japanese securing the strategic facilities at Subic. To prepare for eventual war, the ‘Dewey Drydock’, was towed to Mariveles Harbor, on the tip of the Bataan Peninsula, and scuttled there on April 8, 1941. The worst fears were realized on the 11 December of that year, when Japanese Zero fighter bombers attacked Subic – strafing and destroying seven Catalina naval patrol aircraft in the harbor. Evidence of Japanese intelligence gathering in the area was obvious and reports were being received about the approach of the Japanese Fleet – an invasion was predicted.

By 24 December 1941, the situation at Subic was deemed strategically untenable and orders were given to destroy the station and withdraw. The U.S. military burned down the base, whilst local Filipino residents torched the town of Olongapo. As a final measure, the armored cruiser U.S.S. New York – deemed antiquated and consigned as a floating storeship – was towed into a deep part of the bay and scuttled to deny the Japanese her four 8″ guns. The U.S. Marines withdrew to the Bataan Peninsula and were eventually evacuated under fire to Corregidor Island where they made their last stand before surrendering.

The Japanese Occupation (1941 – 1945)

Throughout World War II, the Japanese Navy maintained a ship-building facility in Subic Bay. The area became infamous for the war crimes committed against Allied prisoners of war – especially for the Baatan ‘Death March’…the forced march of 67,000 U.S. and Filipino prisoners during which many thousands died or were executed… and the tragedy of the Oryoku Maru ‘Hellship’….the prisoner transport ship on which only 400 out of 1360 POWs survived the bombing (by U.S. aircraft), sinking and subsequent mistreatment by the Japanese.

On the 20th October 1944, General MacArthur began the liberation of the Philippines – landing U.S. forces at Palo, Layte. By January 1945, the Japanese had virtually abandoned Subic Bay. Expecting stiffer resistance, the U.S. Fifth Air Force had dropped 175 tons of bombs on Grande Island, but received only light return fire from the skeleton Japanese force remaining there.

General Tomoyuki Yamashita, the Japanese commander in the Philippines, had withdrawn his forces into defensive mountain positions outside of Subic Bay. On the 29th January, 40,000 American troops of the 38th Division and 34th Regimental Combat Team came ashore without resistance at San Antonio, Zambales, advancing on Subic Bay.

They didn’t meet their first resistance until attempting to cross the bridge spanning the Kalaklan River near the Olongapo Cemetery, but that was swiftly overcome and the town was liberated. Sadly, the Japanese, had decided to destroy Olongapo, upon leaving, and left great destruction in their wake.

History of Subic Bay: Post-War U.S. Naval Base (1945 – 1991)

Following the liberation of the Philippines, Subic Bay was designated Naval Advance Unit No. 6, and was home to several submarine and a motor torpedo boat units. Grande Island was re-garrisoned with some 155 mm artillery and anti-aircraft weapons, but no plans were created to return it to the status of a permanent coastal defence installation. By 1963, those guns had returned to the U.S.A. and Grande Island was used solely as an R-and-R area for U.S. fleet personnel.

Whilst independence was granted to the Philippines on the 4th July 1946, the town of Olongapo remained under the administration of the U.S. Navy. This was formalized on the 14th March 1947 , with the signing of the Military Bases Agreement which granted the U.S.A. a 99-year lease for 16 bases or military reservations, including Subic Bay and the administration of the town of Olongapo.

The lessons learned during the Korean War illustrated the critical need for naval air-power – which led to a most ambitious project to develop a Naval Air Station at Cubi Point, in the Bay. This immense task, conducted by the U.S. Navy Seebees began in 1951 and lasted 5 years (20 million man-hours). It was one of the largest earth-moving projects ever conducted (at the time, second only to the construction of the Panama Canal).

Mountains were literally flattened, dense rain-forests felled and vast quantities of earth piled into the sea – to create a 2 mile (3.2km) long runway, air station and adjacent pier. The project costed over $100 million ($718359853 in 2011 dollars) and the facility was finally commissioned on the 25th July 1956. A comprehensive medical facility was also constructed on the base – and the U.S. Naval Hospital, Subic Bay, was opened on 13th July 1956.

Due to U.S. fears about the rising tide of communism in Asia, efforts were made to prevent local resentment and hostility erupting in the Subic area. Over $1.5 million was invested in the town of Olongapo and, on the 7th December 1959, under provisions of the RP-US Military Bases Agreement, the U.S.A. relinquished administrative control of Olongapo town to the Philippines – including some $6 million worth of electrical, water and telecommunications infrastructure.

The steady expansion of U.S. military commitment in the Vietnam War had a significant impact on Subic Bay and the 1960’s saw a massive expansion in the base’s logistical, repair and R&R functions. Over $63 million was invested in developing the infrastructure and facilities during this decade, including a 600 ft extension to Alava Pier, in 1967, to increase berthing capability for the Navy. The record number of U.S. Navy ships berthed in Subic was set in October 1968, when 47 vessels were at harbor there.

The newly constructed Naval Supply Depot handled the largest volume of fuel oil of any Navy facility in the world, processing more than 4 million barrels of fuel oil each month. The depot also supplied Clark Air Base with aviation fuel through a 41-mile (66 km) pipeline. The Cubi Point Air Station Cubi Point served as the 7th Fleet’s primary maintenance, repair and supply center – maintaining over 400 carrier-based aircraft. The facility produced two jet engines per day to supply the demands of the Vietnam air campaign.

The fall of Saigon in the summer of 1975 ;ed to hundreds of thousands of refugees fleeing Vietnam. Many of these refugees were rescued at sea by the U.S. Navy and transported to Subic Bay. A temporary processing centre was set up on Grande Island in 1975, but operations were later moved to the Philippine Refugee Processing Center in Morong, Bataan.

The Naval Air Station was also used extensively during military campaigns in the Middle East, during Operations Desert Storm and Desert Shield.

The 1947 Military Bases Agreement was amended in 1979, asserting Philippine sovereignty over the base area and reducing the U.S. enclosure from 244 to 63 square kilometers.

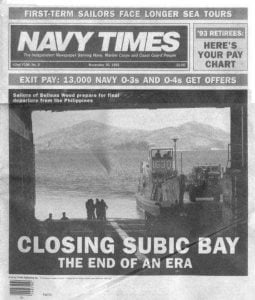

The Withdrawal of U.S. Military (1991 – 92)

On the 15th June 1991, Mount Pinatubo, (32 km from Subic Bay), erupted with a magnitude 8x greater than Mount St. Helens. All daylight disappeared as volcanic ash blotted out the sun. Volcanic earthquakes combined with heavy rain, lightning and thunder from the passing Typhoon Yunya to create a spectacularly ‘hell-like’ impact on the area.

Within 24 hours, Subic Bay had been buried below 30cm of rain-soaked, volcanic ash, causing many buildings to collapse and the loss of electricity and telecommunications. The clean up and repair took many months. The nearby U.S.A.F. base at Clark was declared a total loss and closed – leaving Subic Bay as the U.S. military’s largest overseas defence facility.

However, the base did not remain operational for much longer, as the Philippine’s Senate voted, on the 13th September 1991, to reject the ratification of the ‘Treaty of Friendship, Peace and Cooperation’, which was a pivotal agreement in extending the future lease of American bases in the Philippines.

The U.S.A. and the Philippines continued to negotiate an extension that would allow a prolonged withdrawal of U.S. military, but these talks broke down due to issues with the American withdrawal plans and concerns that the military were storing nuclear weapons in the base area. On the 27th December 1991, President Aquino issued a formal notice for the U.S. military to leave Subic by the end of 1992.

Over the course of 1992, vast quantities of supplies, equipment and transportable facilities were moved out of Subic Bay to other U.S. Navy installations across the globe, including Japan and Singapore. The base was formally closed on the 24th November 1992, and this marked the first time in over 400 years that no foreign military forces were present in the Philippines.

Modern History of Subic Bay: Subic Bay Metropolitan Area (1992+)

In anticipation of the U.S. departure, the Philippine Congress passed Republic Act 7227, on 13th March 1992. This Act was known as the ‘Bases Conversion and Development Act of 1992‘ and served to create the Subic Bay Metropolitan Authority (SBMA) and freeport incentives to stimulate trade and investment through the foundation of the tax and duty-free, Subic Bay Freeport Zone (SBFZ), which was modeled on the freeport areas in Singapore and Hong Kong.

As the final U.S. military departed Subic Bay on the helicopter carrier USS Belleau Wood, the former-Mayor of Olongapo and newly-designated SBMA Chairman, Richard Gordon, took over the facility with the help of 8,000 local volunteers to protect the now-vacant $8 billion facilities, property and infrastructure from looting.

The economy of SBMA has generally flourished since the U.S. military departure, attracting several major foreign companies and causing substantial investment in infrastructure, port facilities and road communications. FedEx’s Asia-Pacific hub, Asia-One, was located in Subic Bay for almost ten years and Korean shipping manufacturer ‘Hanjin’ opened a $1 billion / 543 hectare factory on the west side of the Bay – the 4th largest ship-building plant in the world. Japanese investment also allowed the creation of the Subic-Clark-Tarlac Expressway (SCTEX) that links Clark and Subic Bay – a vital route that allows swift communications.

Other significant companies attracted to the investment haven in the Bay include: Acer, Thompson SA and Enron. Subic Bay also hosted the 4th APEC Leaders’ Summit on the 24th November 1996, during which time the leaders of the world’s 18 most powerful economies, including Bill Clinton, were hosted at a purpose-built venue in Tiboa Bay, close to the former Air Station at Cubi Point.

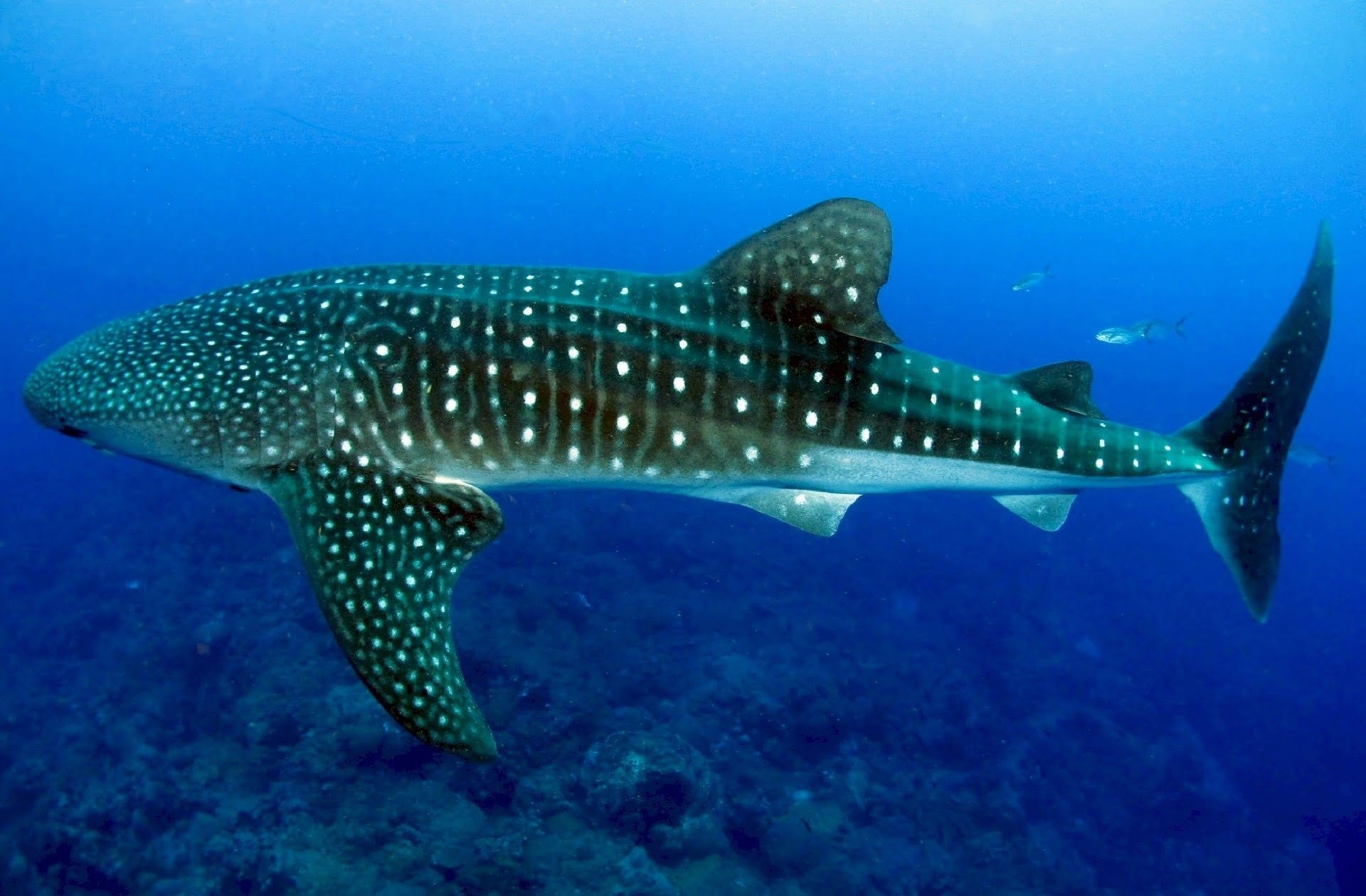

The area is also developing a tourist infrastructure and can boast of many attractions; including several good beaches, scuba diving on world famous ship-wrecks, a jungle survival school, an aquarium and dolphin show, a zoo , a ‘jungle canopy tour’ and many jungle treks and tours.

The modern history of Subic Bay is characterized by ever-increasing commercial expansion within the freeport area, along with increasing tourism on the small beaches fringing the bay.

About the Author

Andy Davis is a RAID, PADI TecRec, ANDI, BSAC and SSI qualified independent technical diving instructor who specializes in teaching advanced sidemount, trimix and wreck exploration diving courses across South East Asia. Currently residing in ‘wreck diving heaven’ at Subic Bay, Philippines, he has amassed more than 9000 open circuit and CCR dives over 27 years of diving across the globe.

Andy has published many magazine articles on technical diving, has written course materials for dive training agency syllabus, tests and reviews diving gear for major manufacturers and consults with the Philippines Underwater Archaeology Society.

He is currently writing a series of books to be published on advanced diving topics. Prior to becoming a professional technical diving educator in 2006, Andy was a commissioned officer in the Royal Air Force and has served in Iraq, Afghanistan, Belize and Cyprus.

Originally posted 2019-02-03 18:20:37.