Overconfidence in Scuba Diving: The Psychology of Diver Hubris

As divers, overconfidence can lead us into dangerous judgments, beliefs, or behaviors; and that same hubris can also spread virally to others. This can have dire consequences with respect to diving safety.

In this article, I will explore how and why divers are prone to overconfidence, its impact on their safety, and the various factors contributing to this phenomenon.

Overconfidence is a Common Delusion

Psychology studies often reveal a curious human quirk: we tend to overestimate our abilities. For example, a staggering 93% of people believe they are better than average drivers. Yet, statistically, that is an impossibility.

In his book ‘Human Error‘, psychologist James Reason investigated driving errors.

- Out of 520 drivers interviewed, only five participants (<1%) admitted to below-average driving skills.

- The rest, even those with a track record of accidents, considered themselves at least as good as others, with many claiming superiority.

We consistently perceive ourselves as more intelligent, creative, athletic, skillful, considerate, honest, and friendly than most people.

Today, psychologists continue to document similar overconfidence across various traits and abilities. This phenomenon raises intriguing questions about how and why we succumb to such unwarranted confidence.

What makes people overconfident?

People can become overconfident due to various factors, including cognitive biases and social, cultural, and gender influences.

The Better-Than-Average Effect

The Better-Than-Average Effect (BTAE) is a well-documented cognitive bias in social psychology. It revolves around our natural inclination to view our abilities, attributes, and personality traits as superior to those of the average person.

The BTAE, closely related to the ‘illusory superiority‘ cognitive bias, was coined by researchers Van Yperen and Buunk in 1991. It’s known by various names, including the above-average effect, the superiority bias, the leniency error, the sense of relative superiority, the primus inter pares effect, and the Lake Wobegon effect.

Research into the BTAE shows both positive and negative effects. On one hand, those exhibiting this bias tend to have higher self-esteem and lower levels of depression. On the other hand, it can lead to unrealistic optimism and a failure to recognize risks.

The roots of the BTAE lie in motives for self-enhancement and the desire for positive self-regard, making it a prevalent aspect of human perception that influences decision-making and behavior.

Understanding the Better-Than-Average Effect is essential as it unveils the complexities of self-perception and the biases shaping our self-concept in a world where, logically, not everyone can be above average.

Selective Measuring

Selective Measuring, or Selective Recruitment, describes psychological processes that favor the individual when using comparisons to others when estimating their ability. This can include:

- Comparing one’s own strengths against other people’s weaknesses.

- Evaluating one’s performance against lower-ability peers.

- Gauging one’s performance in comparison to a fictional ‘average person’ of assumed lower ability.

Unconsciously seeking flawed comparisons has the effect of raising the individual’s estimate of their own ability.

The Downing Effect

The “Downing Effect” is attributed to C. L. Downing, a researcher renowned for conducting pioneering cross-cultural studies on perceived intelligence. His investigations further unveiled a correlation: the capacity to precisely assess others’ IQs was directly correlated to one’s own IQ level.

- Those with lower IQ are less capable of accurately appraising other people’s IQs.

- People with high IQs are better overall at appraising other people’s IQs.

While specific to IQ, and similar to the Dunning-Kruger Effect, this phenomenon hints at how overconfidence manifests in other areas.

Lack of Critical Feedback

A scarcity of candid negative feedback also contributes to overconfidence. Genuine, constructive feedback is rare, as people avoid delivering negative comments.

This absence of helpful feedback hinders self-improvement. As David Dunning notes, “Feedback is often nonexistent or ambiguous. What people say to our face tends to be more positive than behind our backs.“

Positive feedback in training can significantly contribute to performance overestimation, especially when individuals already possess overconfidence and low self-awareness. Several key mechanisms play a role in this phenomenon:

- Selective Attention: When individuals receive positive feedback, they tend to focus on the aspects that confirm their strengths while downplaying their weaknesses.

- Low Self-Awareness: Individuals with low self-awareness are less likely to critically evaluate their performance. This will amplify the effect of selective attention.

- Confirmation Bias: Positive feedback reinforces a confirmation bias where overconfident people actively seek information which reinforces preconceived notions of their abilities. They may ignore or dismiss feedback that suggests otherwise.

- Reinforcement Loop: This process creates a reinforcement loop where positive feedback bolsters overestimation and overconfidence, leading individuals to seek out more validation and further confirm their inflated self-perceptions.

In contrast, when individuals only receive constructive negative feedback, they are more likely to recalibrate their self-assessments, leading to a more accurate perception of their abilities and performance.

Superiority Bias Explained

Overconfidence is Contagious

Research by psychologist Joey Cheng in 2021 highlights the contagious nature of overconfidence. Cheng’s study reveals that exposure to overconfident individuals can lead others to overestimate their own abilities within a social group, potentially fostering dangerously misguided thinking within teams.

- Individuals adjust their self-assessments based on the confidence displayed by their peers.

- Observing overconfident peers significantly increases an individual’s own perception of ability.

- When exposed to exceptionally overconfident individuals, participants tended to inflate their perceived ranking by approximately 17%.

- Conversely, those exposed to more realistic peers tended to underestimate their rank by around 11%.

Cheng’s research identified a “cascade effect“, where the illusion of superiority could be transmitted from one person to another within a group.

Additionally, a “spill-over effect” was observed, suggesting that exposure to overconfidence in one domain could lead to increased arrogance in other areas.

Our findings suggest that some of that [overconfidence] might have been due to this social contagion effect, and that could have led many individuals to have adopted the questionable practices that contributed to its downfall. Leaders and managers need to be very mindful of the effects of certain individuals on others, because their overconfidence could really spread widely.

Joey Cheng, The Social Transmission of Overconfidence.

Disturbingly, these consequences persisted long after the initial interaction, with just a few minutes of exposure to an arrogant individual skewing participants’ judgments for days.

This highlights the significant impact of overconfidence as a social contagion, potentially influencing divers to adopt questionable practices. You should be acutely aware of the profound effects certain individuals can have on you.

Gender Differences in Overconfidence

Males and females frequently demonstrate variations in self-confidence, with notable implications for decision-making. A significant study by Niederle and Vesterlund in 2007 found that women tend to avoid competition, while men actively embrace it.

Furthermore, research on professional freedivers strongly supports these overconfidence disparities.

- On average, females are 18% less likely to display overconfidence.

- This limits risk-taking judgments compared to males.

- However, females may experience more overconfidence concerning relative performance with other competitors.

In contrast;

- Men often develop higher inclinations towards overconfidence as a reaction to an increase in competition.

- However, they tend to more readily adjust their confidence levels when negative incidents are encountered.

- Adverse incidents like shallow water blackouts, play a pivotal role in refining self-confidence accuracy.

Cultural Differences in Overconfidence

Cultural variances exert a significant influence on an individual’s inclination towards overconfidence. Culture plays a vital role in shaping and expressing motivations. Different cultures have distinct values, norms, and social expectations that influence what drives individuals.

A comprehensive meta-analysis encompassing 70 studies that assessed the levels of self-enhancement or self-criticism in China, Japan, and Korea compared to the United States and Canada underscores the substantial disparities between these two cultural paradigms.

Westerners showed a clear self-serving bias, whereas East Asians were more self-critical and less inclined to self-enhance.

Notably, Americans tend to magnify their self-assessments. A 2007 psychology study suggests that this is linked to goals of improving self-esteem and self-enhancement.

In contrast, Asian cultures lean towards the opposite end, often underestimating their capabilities with the goal of personal improvement and harmonious relationships.

“As Western society becomes more individualistic, a successful life has come to be equated with having high self-esteem. Inflating one’s sense of self creates positive emotions and feelings of self-efficacy, but the downside is that people don’t really like self-enhancers very much.”

Heine, S. J. (2007). Culture and motivation: What motivates people to act in the ways that they do?

A 2007 study also demonstrated that when Americans perceive a lack of proficiency in a particular domain, they often opt to switch their focus to something else. In contrast, Asians interpret subpar performance as an opportunity to redouble their efforts and strive for improvement.

Consequences of Overconfidence as a Diver

Overconfidence among divers can lead to risky decisions, flawed risk management, and a dismissal of peer feedback and expert advice. Such behavior increases the likelihood of accidents and violations of dive safety standards, putting lives at risk.

- Overestimation of Abilities: Overconfident divers tend to overestimate their own abilities and knowledge. In the context of diving risk assessment, this can lead to taking on more complex dives than warranted, believing they can handle situations that are beyond their capability.

- Poor Decision-Making: Divers with excessive confidence may make hasty decisions without thoroughly considering potential risks and consequences, increasing the likelihood of accidents.

- Ignoring Contrary Information: Overconfident divers often dismiss or ignore information that contradicts their beliefs or decisions. This confirmation bias can prevent them from recognizing and mitigating risks effectively.

- Interpersonal Conflicts: Overconfidence can negatively affect diving teamwork by creating friction, as overconfident individuals may be less receptive to others’ input or ideas.

- Failure to Learn from Mistakes: Overconfident divers are less likely to admit their errors and learn from them, which can perpetuate risky behaviors and decisions over time.

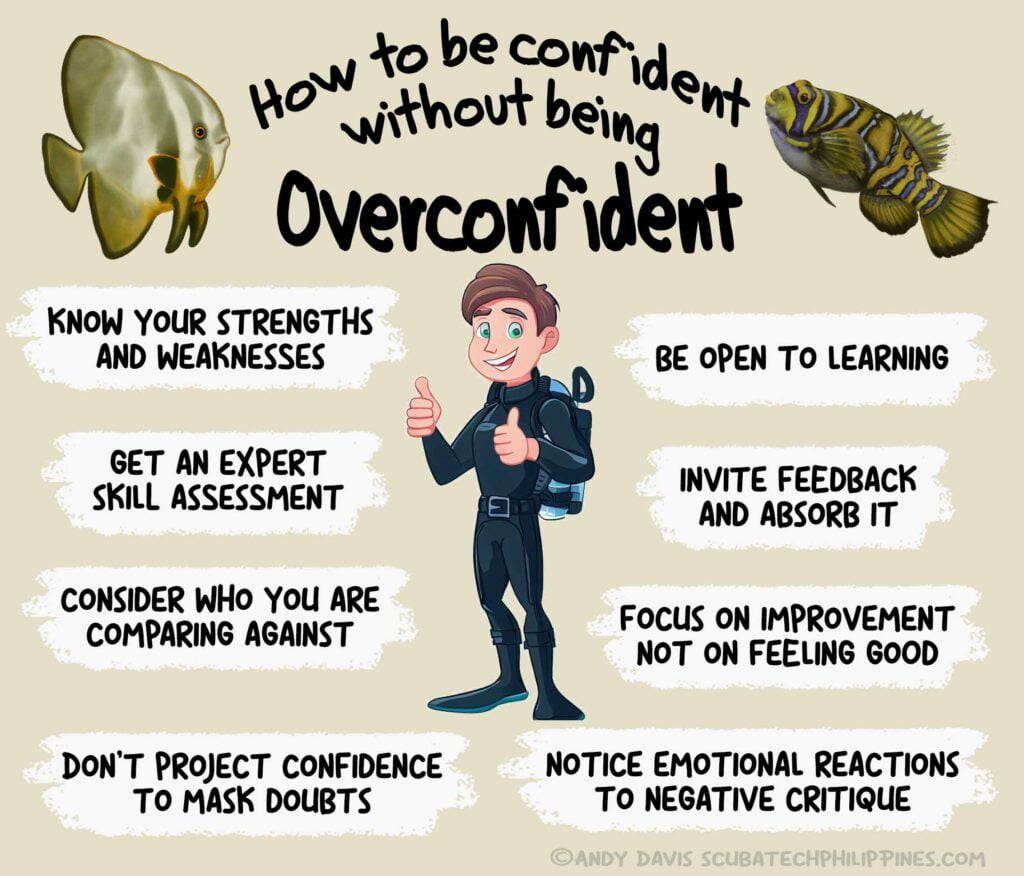

Recognizing Overconfidence as a Diver

To enhance your safety and competence as a diver, it’s vital to examine your attitudes, particularly your perception of your diving proficiency. Inflating your skills without a solid foundation not only increases your personal accident risk but also spreads overconfidence within your diving community.

Understanding how cognitive bias can foster overconfidence is crucial.

Comparison with other divers

When evaluating yourself, especially when objective assessments are unavailable, be cautious of relying on social comparisons. Questions like “What defines an average diver?” become challenging without concrete data.

In the absence of such data, you face a choice. For example:

- Upward comparison: e.g. comparing yourself with elite level divers, like Shek Exley.

- Downward comparison: e.g. comparing yourself with newly qualified Open Water Divers.

You need to be mindful about who you choose to compare yourself against. It needs to be realistic and relative, not ego-gratifying.

Generally, it is more productive to compare oneself against better divers than worse ones.

However, a too-high comparison can serve the unintended consequence of unrealistically diminishing your confidence; especially if the comparison is made to a specialist diving activity that you perceive as difficult.

Remember that we are prone to constructing fictional ‘average divers’ of lower ability to reinforce our confidence.

Objective versus Subjective Self-Evaluation

Unlike fields with objective benchmarks, such as competitive sports, business, or medicine, scuba diving lacks standardized objective comparisons. This means that divers have to rely upon subjective self-evaluations, which are susceptible to error and bias.

It is easy to objectively gauge your ability against a record-breaking athlete or sportsperson. Can you run as fast, jump as high, or score as many points? Only the very delusional fail in this.

In contrast, it is very difficult to ascertain how you might be lacking compared to a higher-level diver, and the dives they undertake.

The only objective ability feedback you might receive as a diver is when an accident or near-miss occurs.

Well-calibrated confidence, based on accurate assessments, is the ideal goal for any diver. To ensure an accurate grasp of your ability, seek expert external validation, such as standardized performance benchmarks like the GUE Fundamentals course.

While it can boost confidence to believe you’re above average, diving’s inherent risks make it a double-edged sword. A confident mindset helps expand your comfort zone, however, it can shatter self-confidence when a negative incident happens because you overestimated your ability.

The Pros and Cons of Overconfidence in Diving

Overconfidence in scuba diving can be a double-edged sword. While it can boost a diver’s confidence and motivation, it may lead to risky behavior and hinder skill development.

The Pros of Overconfidence in Diving

Overconfidence can:

- Boost divers’ self-esteem.

- Increase optimism of positive outcomes.

- Promote expanding comfort zones.

- Encourage divers to set higher goals and strive for continuous improvement.

- Increase dive leadership ability.

- Reduce stress during uneventful circumstances.

The Cons of Overconfidence in Diving

Overconfidence can:

- Lead to risky behaviors that result in diving accidents.

- Lower risk aversion as a trait.

- Reduce the accuracy of risk management.

- Make divers less receptive to feedback from experienced individuals.

- Allow stagnation in skill development.

- Cause panic when a real-life incident occurs.

Striking a balance between confidence and humility is essential for safe and enjoyable scuba diving. Acknowledging that overconfidence can occur and actively seeking continuous education and skill development can contribute to safer dives.

Understand Overconfidence as a Diver

This article has explored the intricate interplay between diver psychology and overconfidence, emphasizing the significance of self-awareness and risk management.

Scuba diving is not just about mastering the skills but also about recognizing the limits of our abilities. Understanding the pitfalls of hubris underwater is the first step towards safer and more enjoyable dive adventures.

By acknowledging the psychology behind overconfidence, divers can make informed decisions, prioritize safety, and ensure that their underwater escapades remain awe-inspiring and incident-free.

So, remember, a conscious diver is a safe diver, and the wisdom gained from this exploration can lead to a lifetime of fulfilling and secure scuba diving experiences.

Purchase my exclusive ebook!

A comprehensive guide to the mindset and psychology of diving excellence.

$20 Printable PDF Format, 298 pages

Psychology of Overconfidence References

The better-than-average effect in comparative self-evaluation: A comprehensive review and meta-analysis. Zell, E., Strickhouser, J. E., Sedikides, C., & Alicke, M. D. (2020) Psychological Bulletin

The Better-Than-Average Effect Is Observed Because “Average” Is Often Construed as Below-Median Ability. Kim, Young-Hoon & Kwon, Heewon & Chiu, Chi Yue (2017) Frontiers in Psychology

Deconstructing the better-than-average effect. Guenther CL, Alicke MD (2010) Journal of Personality and Social Psychology

The social transmission of overconfidence. Cheng, J. T. et al.(2021). Journal of Experimental Psychology

Miscalibration in predicting one’s performance: Disentangling misplacement and misestimation. Engeler, I., & Häubl, G.(2021) Journal of Personality and Social Psychology

Lake Wobegon be gone! The “below-average effect” and the egocentric nature of comparative ability judgments. Kruger J. (1999) Journal of Personality and Social Psychology

Human error. Reason, J. (1990) Cambridge University Press.

Gender differences in overconfidence and

decision-making in high-stakes competitions:

evidence from freediving contests. Lackner M. & Sonnabend H. (2020) VfS Annual Conference 2020: Gender Economics, German Economic Association.

In Search of East Asian Self-Enhancement. Heine, S. J., & Hamamura, T. (2007) Personality and Social Psychology Review

Why arrogance is dangerously contagious. David Robson (2020) BBC Worklife, Psychology

How can we judge how good we are in sport? Are we better-than-average? (2021) Sporting Bounce

Why we overestimate our competence. Tori DeAngelis (2003) American Psychological Association

Above-Average Effect: Why People Feel Better Than Average. Dr Jeremy Dean (2023) Psyblog

The Worse-Than-Average Effect: When You’re Better Than You Think. Dr Jeremy Dean (2012) Psyblog

About The Author

Andy Davis is a RAID, PADI TecRec, ANDI, BSAC, and SSI-qualified independent technical diving instructor who specializes in teaching sidemount, trimix, and advanced wreck diving courses.

Currently residing in Subic Bay, Philippines; he has amassed more than 10,000 open-circuit and CCR dives over three decades of challenging diving across the globe.

Andy has published numerous diving magazine articles and designed advanced certification courses for several dive training agencies, He regularly tests and reviews new dive gear for scuba equipment manufacturers. Andy is currently writing a series of advanced diving books and creating a range of tech diving clothing and accessories.

Prior to becoming a professional technical diving educator in 2006, Andy was a commissioned officer in the Royal Air Force and has served in Iraq, Afghanistan, Belize, and Cyprus.

In 2023, Andy was named in the “Who’s Who of Sidemount” list by GUE InDepth Magazine.

Purchase my exclusive diving ebooks!

Originally posted 2023-09-23 19:33:18.