Sheck Exley’s Razor – The Nature of Diving Limits, by R.D. Milhollin

(Blog editor’s note: This Sheck Exley article was first published in the March-April 1995, issue of Underwater Speleology. I have added it here on my blog to preserve and disseminate further, what I believe to be beneficial insights into overhead and technical diving knowledge).

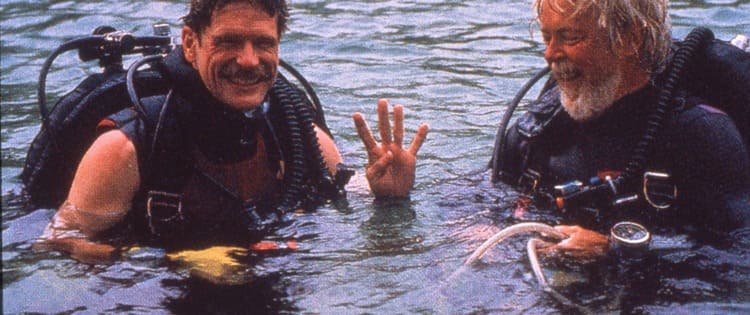

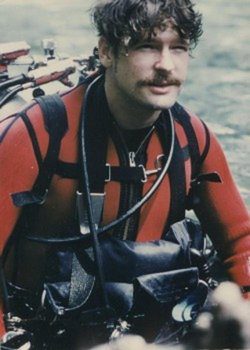

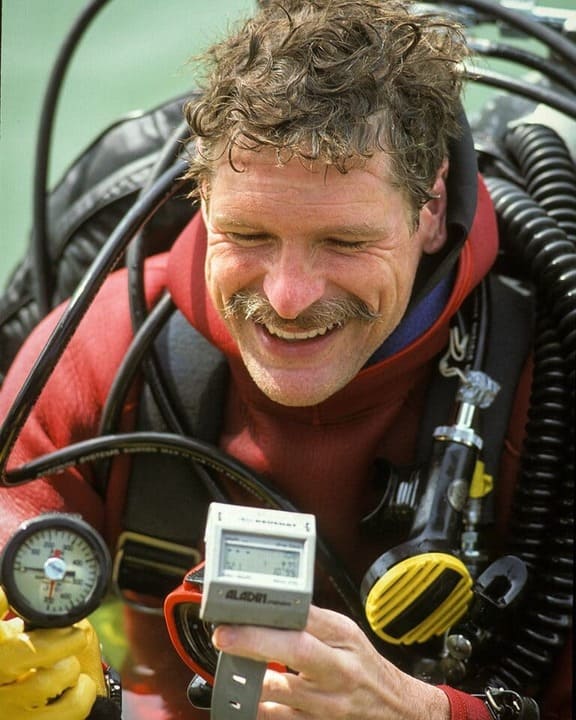

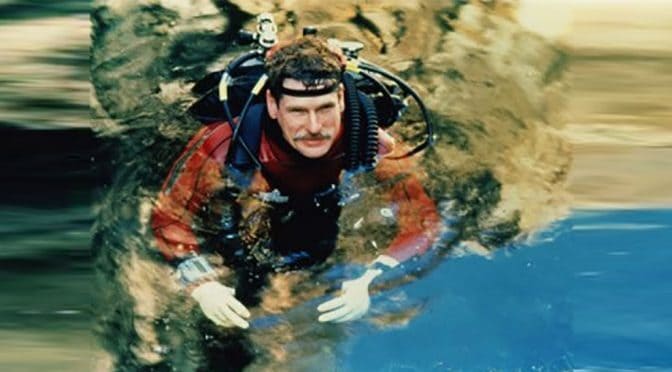

Sheck Exley

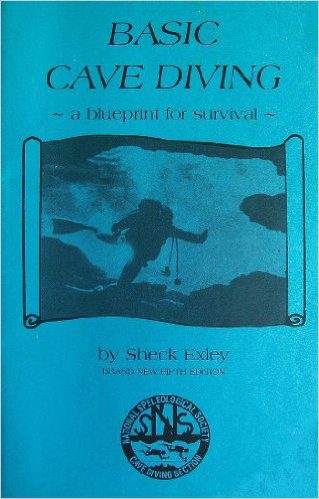

Sheck Exley was one of the most outstanding explorers of his time. Within the field of cave diving, he was virtually peerless. He was concerned from the early days of the practice with identifying factors involved in cave diver deaths. Exley was one of the first to use an analytical approach to assess the causes of cave diver failure. His actions helped define many of the commonly held limits in this field today. His business was limits. And he died diving in a cave.

One never truly knows one’s limits until they are encountered. Once a limit is reached and exceeded, return is not always possible. This razor is dangerously sharp. It divides those seeking the knowable end from those who have found the ultimate destination.

Sheck Exley

Occam’s Razor

Occam’s (or Ockham’s) razor is a principle formulated by William of Ockham, stating that terms, concepts, assumptions, etc. must not be multiplied beyond necessity. It is a limiting and simplifying guideline for inquiry and explanation, advocating parsimony over complexity. The admonishment to science has guided inquiry for over 600 years.

Exley’s Razor

Exley’s Razor is a proposal for discussion involving the nature of limits. One never truly knows one’s limits until they are encountered. Once a limit is reached and exceeded, a return is not always possible. This razor is dangerously sharp. It divides those seeking the knowable end from those who have found the ultimate destination.

The problem posed by this proposition holds great importance for the pursuit of cave diving. Some of the basic admonitions given to the student entering this pursuit deal with limits, specifically those of depth, horizontal penetration, gas supply, and reserve gas.

The implications of breaking these limits are often assumed to be understood. They are probably better appreciated during the first few penetrations into an overhead environment than later, after a few dozen dives have been successfully completed. The idea of limits in cave diving can be approached in many ways and may assume the following forms:

- horizontal penetration

- vertical depth achieved

- hours submerged

- distance traveled

- speed of travel

- gas supply and consumption,

- gas component depth/time considerations (i.e., PO2 depth)

- fatigue

- physical and emotional stress

- task complexity

- equipment considerations.

Limits during training

Limits are imposed on students during training, and are impressed on novices by the cave diving community.

- There are limits imposed by landowners, by physics, and by the legal system.

- There are limits that are self-imposed, such as those related to practical, financial, or physical comfort.

- Some limits may be dictated by body size or health and fitness considerations.

The limits to be addressed here are primarily those involving experience, mental and emotional states, family considerations, personal safety, and internal feelings of security.

By analogy, limits may be envisioned as the ability of a particular material to recover its shape after being deformed by applied stress, a measure of tensile ability. Past some point, the material will either break (fail) or will not be able to return to its original shape. Every cave dive involves stress in one or more of its forms, and the diver must strive to avoid reaching and exceeding the type of limit he might not be able to return from.

Caverns Measureless to Man is the story of the passion of an extraordinary individual who spent his life exploring underwater caves. For nearly 30 years Sheck Exley was the leader. He set records, he developed the techniques, and he maintained the highest standards of excellence.

Psychology & ego

The least well-known aspect of cave diving is the psychological. There are now and have been divers who will do things on a dare. For these people the ego may be fragile: once the ego is threatened, it can lead them into areas they know to be unsafe.

The ego threat, if not controlled, can cause divers to exceed their own known limits of comfort.

The fact that another diver completed a particular dive can be reason enough for the threatened ego of a weak individual to justify taking risks that might otherwise be avoided.

A cave diver wishing to keep this potential threat under control might consider including “motivation” as part of the formal pre-dive planning process. This could help by providing an opportunity for the diver to assess the reason they want to attempt a particular profile, and a chance to modify that profile if sufficient justification is lacking.

By consciously considering the reason for choosing to attempt a particular dive, the diver is making the first step toward defining and enforcing the personal limits that will enable him or her to be comfortable while undertaking this demanding pursuit.

It may be possible for properly trained (to standards) but ill-informed novices to get a false impression of how more experienced cave divers became that way. They see individuals going through training from beginning students to “full cave” certified in a surprisingly short amount of time and assume this must be the best route to take.

Before my highest mountain I stand and before my longest wondering: To that end I must go down deeper than I ever descended.

Zarathustra, F. Nietzsche

Instant gratification

The instant gratification expected by the children of the instant culture of the 1950’s onward comes into play. Mix a newly certified diver, lots of money (equipment), and the right amount of encouragement (from the instructor or through the social environment), and you have the potential for a cave diving statistic. Just add water!

The fact that some lucky individuals actually survive while taking poorly calculated risks can boost confidence in underdeveloped skills and abilities, blinding them to the reality of their limited developed potential. There are novices who can see no difference between themselves and a diver who has been actively and patiently honing skills for 20 years or longer, building up a vast reservoir of reflexes and insights that will be there when needed.

The dividing line between the successful and the not-so-lucky will not be seen on the ideal dive, but instead, on the dive that had a problem.

The experienced diver will know how to react when things begin going badly and will be better prepared to recover the presence of mind in time to make the crucial decisions that will save his life. This observation should be borne in mind by all cave divers, who must inevitably assess their own capabilities and set their own personal limits.

These limits must be set based on the worst possible circumstance imaginable, not upon what is likely to be expected. Only by allowing the unthinkable to enter into consideration can the serious cave diver expect to survive the unlikely.

Recreational cave divers vs. cave diving explorers

There should be a division drawn between the recreational cave diver and the cave diving “explorer,” for lack of a better term.

It is recognized that exploration assumes a wide spectrum of activity, and the term is applied in this instance to denote the highly experienced diver who has been expanding his or her capabilities to significant levels over a considerable period of time and has made a conscious decision regarding the importance of cave diving in his or her life.

The true explorer must carefully and continually assess the limits of his pursuit, allow them to change depending on any number of factors, and keep them always in mind.

To how many cave divers does this apply? How many are truly willing to take the chance and walk the razor’s edge? Probably not a lot if it really gets down to serious thought about consequences. Perhaps that is what is needed: serious thought among cave divers.

This process should probably begin at the earliest level of instruction when the effects of inappropriate decisions or poor technique are explained. An appropriate observation is that when things begin to go bad in one area, there seems to be an escalating number of things that go wrong or appear to go wrong in other areas. If this process is not stemmed in time, the result will ultimately be diver failure.

Of course, in cave diving, this almost always indicates death. There is little possibility of escaping with injury. It is no accident that the open water training sequence features rescue practice while cave diving has a course in body recovery.

The commercialization of cave and technical diving

The commercialization of cave and other forms of “technical diving” makes this discussion even more difficult than would otherwise be the case. The proliferation of “professional” instructors carries with it the implicit fact that they must earn a living and are hence prone to advertise their services to the general public, and may be less apt to deny a student with marginal skills or a poor attitude access to a course.

The rent needs to be paid. Encouraging students to participate in cave diving courses not only defeats any serious attempt at screening for personality types not suited to the pursuit but invites much greater damage to the cave environment than is absolutely necessary for training and learning. There is a cost associated with the commercialization of cave diving that may not be readily apparent except to those willing to look past personal objectives to see the greater whole.

The traditional cave courses were not openly advertised and students were not sold this form of diving as a product. Both of the major training organizations have discouraged the “promotion of cave diving,” but have shied away from defining what “promotion” is specifically. New cave divers were once expected to systematically work their way from simple dives to more complex dives, slowly, over time.

Progressive penetration

The idea of “progressive penetration” was espoused by those who had learned that way, and had accumulated impressive numbers of successful dives following this dictum. Of course, in the early days of cave diving, the idea of a serious dive was something much different than what is commonly imagined today.

Some of the early pioneers racked up thousands of cave dives over relatively short periods of time, for these were quite short penetrations by today’s standards. There have always been those who tested the limits, as can be attested to by the exploits of Wally Jenkins and his Wakulla Springs team, among many others.

Given the same circumstances, it is unlikely that many of today’s experienced cave divers would be able to (or want to) accomplish the same feats that were undertaken in the 1950’s and 1960’s.

Given the nature of cave diving limits, recreational cave divers should stay well away from where they feel their own limits might be to avoid the possibility of exceeding them. But how is one to know where those limits lie?

As mentioned previously, students and novices have the benefit of ready-made limits handed down by more advanced and capable practitioners who have successfully gone through the learning process themselves.

Accident analysis

It should also be pointed out that the basic rules of accident analysis were derived from the observations of circumstances surrounding those who were not as successful. As the novice progresses, and experiences gained through time spent in the pursuit begin to add to his or her confidence and abilities, the task of redefining limits is encountered.

How this is done is largely a personal matter, but it is likely that an honest appraisal of one’s physical abilities and overall preparedness would allow most to define reasonable limits. Adherence to these standards, once drawn, is again a matter of personal integrity, and when to enlarge the scope of what one allows oneself to do is strictly subjective, for limits must be expanded as the diver grows.

Goals vs. limits

The immediate importance of achieving a goal can lead to extending beyond where one feels comfortable or safe; this is what needs to be avoided. Do limits need to be reviewed? Should the community address the subject of specifically recommended limits for novices versus “explorers”?

One suggestion might be to have novices complete personal inventories during cave diving training detailing all they may have to lose if they were to die as a result of exceeding their limits. Spouses, children, other family, careers, material possessions, the opportunity to make other dives, etc. would invariably crop up during this process and could help the introspective student realize the importance of adhering to known safe standards.

Students and novices gaining experience should ask themselves honestly how they rate in terms of cave diving wisdom and set their personal limits accordingly. The community might consider an attempt to further define limits for recreational versus exploration dives in terms of decompression times, number of cylinders, or any other arbitrary recommendations, but the ultimate responsibility for personal safety and comfort lies with the diver.

Explorers have to set limits just as novices do, but they have more knowledge, time, and experience under their belts, are generally capable of more efficient swimming, and have mastered more advanced techniques. These are personal decisions with profound consequences.

The nature of this type of decision is what should be provided to the student and novice through course content, the example of other divers, and possibly through signs similar to the type used to warn untrained individuals of the general dangers of cave diving”.

Diving recommendations

The recommendations of any outside group, whether governmental, training agency, diving community, or more experienced friends, will ultimately be just that: recommendations. We must realize that the best of recommendations are easily disregarded by the irresponsible and that unfortunately the training of recovery divers will still be needed in the foreseeable future.

Sheck Exley exemplified the ideal cave diver to many people. His experiences are well documented through his years of service to the NSS-CDS and to Underwater Speleology. His discoveries and successful ventures earned him the admiration of a diverse set of communities, from adventure seekers to scientific investigators.

It is not ironic that his death can be looked upon as a source of information to be used to inform other cave divers, for this process is exactly the contribution that he made to the understanding of cave diving deaths. Exley’s findings are not written in stone. They are subject to update. There is a blank space remaining under the fifth rule of accident analysis.

Purchase my exclusive ebook!

A comprehensive guide to the mindset and psychology of diving excellence.

$20 Printable PDF Format, 298 pages

About The Author

Andy Davis is a RAID, PADI TecRec, ANDI, BSAC, and SSI-qualified independent technical diving instructor who specializes in teaching sidemount, trimix, and advanced wreck diving courses.

Currently residing in Subic Bay, Philippines; he has amassed more than 10,000 open-circuit and CCR dives over three decades of challenging diving across the globe.

Andy has published numerous diving magazine articles and designed advanced certification courses for several dive training agencies, He regularly tests and reviews new dive gear for scuba equipment manufacturers. Andy is currently writing a series of advanced diving books and creating a range of tech diving clothing and accessories.

Prior to becoming a professional technical diving educator in 2006, Andy was a commissioned officer in the Royal Air Force and has served in Iraq, Afghanistan, Belize, and Cyprus.

In 2023, Andy was named in the “Who’s Who of Sidemount” list by GUE InDepth Magazine.

Purchase my exclusive diving ebooks!

Originally posted 2018-03-07 23:55:22.