Pony Cylinders and Redundant Air Sources for Wreck Diving

Recreational wreck divers often question whether they need to carry pony cylinders, or another redundant gas source when conducting specialist wreck diving activities. Most agencies and instructors will generally recommend the use of redundant air sources to be a prudent measure for wreck divers. However, the use of redundant air sources isn’t a mandatory requirement; so how can scuba divers decide for themselves whether they should equip themselves with a pony cylinder?

What are pony cylinders in diving?

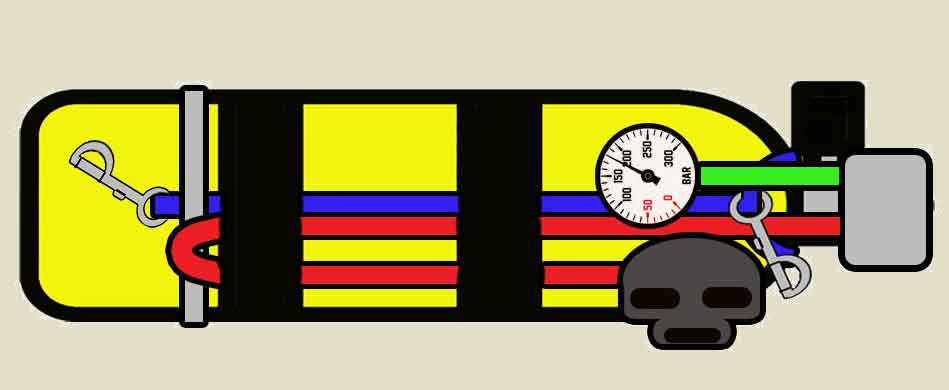

Pony cylinders are additional small cylinders carried by scuba divers as a contingency for out-of-gas emergencies. Pony cylinders have their own dedicated regulator and are considered a redundant gas source.

How are pony cylinders carried?

There are two common methods for carrying pony cylinders; clamped to the primary cylinder at the rear or hung by boltsnaps from D-rings on the divers’ BCD at the front.

Clipped onto shoulder and waist D-rings with bolt snaps

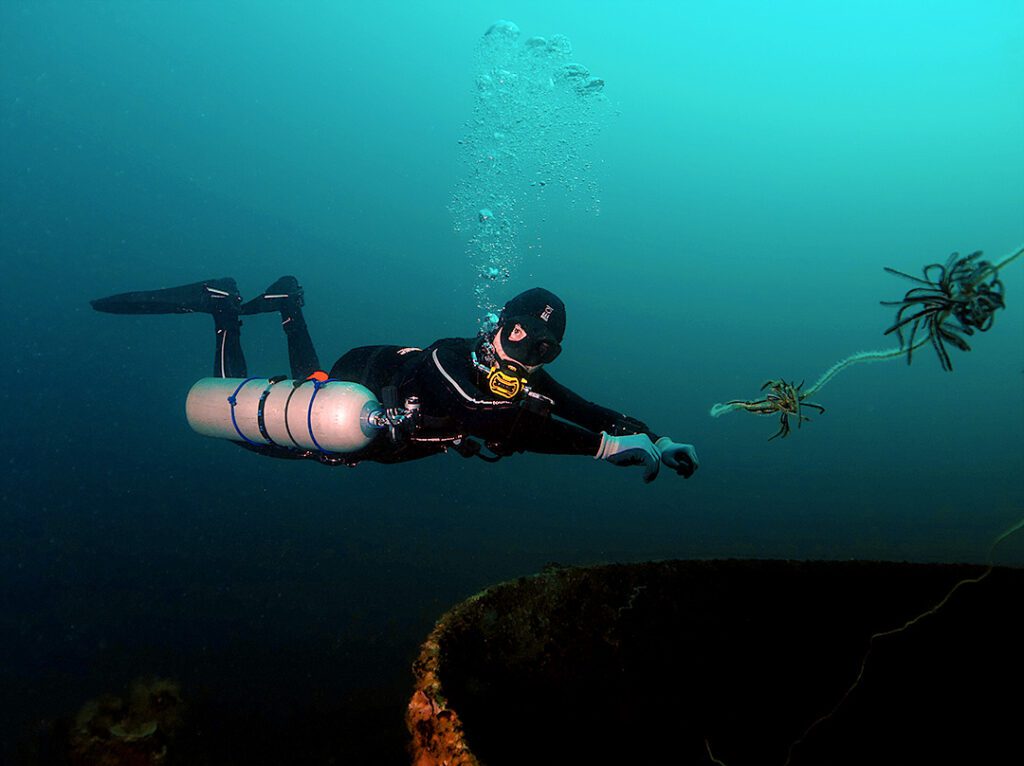

Clipping pony cylinders to the front of the BCD, via shoulder and waist D-rings, tends to be more popular with experienced divers. This method gives a lot more flexibility; including the ability to observe any leaks from the system, retain clean hose routing and detach the cylinder at any time during the dive; enabling it to be donatable to other divers should the need arise.

To configure pony cylinders for front carry, you can buy a stage bottle kit. These include bolt snaps at the neck and side of the cylinder, along with a worm-type clamp, nylon carrying handle and rubber hose retainer bands.

You could also make your own stage bottle kit from rope and individual hardware components bought from a dive shop.

Backplate/wing-style BCDs are an ideal choice if using pony cylinders with this configuration; the harnesses have the D-rings in the right places.

For wreck penetration, having the pony cylinder in front can also avoid delicate equipment from suffering accidental collisions with the wreck.

Pros

- The cylinder valve can be manipulated during the dive

- Gas leaks can be seen

- No hose clutter

- Removeable and donatable during the dive

Cons

- Needs sturdy BCD D-rings as attachment points

- Slightly more complex to use

Clamped to the primary cylinder at the rear

Clamping the pony cylinder to the primary tank at the rear is a very popular option with recreational divers.

The location is unobtrusive, but care has to be taken to differentiate the pony cylinders’ SPG and regulator second stage from the divers’ primary ones. Confusion could lead to a gas depletion emergency.

This method does not demand sturdy D-rings on the BCD shoulder and waist straps. The diver cannot manipulate the pony cylinder valve, so they cannot shut it down if it leaks, or open it in water if they neglect to turn it on pre-dive.

Pros

- Doesn’t require a BCD with sturdy shoulder and waist D-rings.

- Unobtrusive location

Cons

- No access to the cylinder valve

- More hose clutter when diving

- Risk of confusion with primary cylinder regulators

You can purchase a variety of metal or nylon webbing clamp systems to secure pony cylinders onto your main tank.

In general, metal clamps are preferable because they are more robust. Some models feature quick-release brackets.

What regulators to use with pony cylinders?

A regulator used with pony cylinders consists of a first-stage, second-stage and an SPG. You can use a full-size SPG, or some divers are content with a button-sized gauge. A 6-9″ high-pressure SPG hose is ideal for front-staged pony cylinders. For back-clamped ponies, a full-size 30″ HP hose is necessary.

A few diving manufacturers sell dedicated regulator sets for use with pony cylinders, or you can make your own.

The main criterion for a pony cylinder regulator is reliability. The system is for emergencies and, if needed, your life will rely upon it.

What size should a pony cylinder be?

Pony cylinders should provide enough volume of gas calculated to be sufficient for a safe ascent and safety stop. An adequate volume for pony cylinders is typically one-quarter to one-half the gas volume of the primary cylinder volume; i.e. a 3L (AL19), 4L (AL30) or 6L (AL40) cylinder if using an 11L (AL80) volume primary cylinder.

The exact ideal volume of pony cylinders is relative to the diver’s Surface Air Consumption (SAC) rate and the depth they will dive to. Higher-quality diving courses teach student divers how to calculate those requirements precisely.

Metric pony cylinder specifications

AL19

Metric water volume 2.7L

Gas volume@200bar 540L

AL30

Metric water volume 4.3

Gas volume@200bar 860L

AL40

Metric water volume 5.7L

Gas volume@200bar 1140L

Gas Management For Scuba Divers

The comprehensive, illustrated, metric guide to advanced gas planning and management for safer scuba diving. Only $9!

60 Pages. Printable PDF format. Fully Illustrated.

Calculating minimum pony cylinder volume for ascent

Direct ascent to the surface

For this calculation, it is prudent to allocate 1 min at bottom depth, a safe 10m/min ascent rate, and completion of a 3 min safety stop at 5m, followed by an ascent to the surface at a slower 5m/min ascent rate.

This calculation is known as Rock Bottom Gas Management. It incorporates the conservative assumption that the diver/s require some time at the bottom depth to gather their senses or deal with any issues before initiating their ascent. It also plans for the diver to ascend at a normal safe ascent rate, completing their safety stop and then ascending at half normal ascent speed to the surface.

In this example, I have assumed the diver has a SAC rate of 30L/min (lower than average) and a bottom depth of 30m/100′.

Ascent Phase | Avg Depth | ATA | SAC | RMV | Time | Gas Vol Consumed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

1 min bottom | 30m | 4 | 30L/min | 120L/min | 1 min | 120L |

Ascent to safety stop | 17.5m | 2.75 | 30L/min | 82.5L/min | 2.5 min | 206L |

3 min safety stop | 5m | 1.5 | 30L/min | 45L/min | 3 min | 135L |

Ascent from stop | 2.5m | 1.25 | 30L/min | 38L/min | 1 min | 37.5L |

Total gas 499L | ||||||

(depth – stop depth) ÷2 + stop depth | (Depth÷10) +1 | Diver calculated | ATA x SAC | Time at Avg Depth | RMV x Time |

Using that example of SAC 30L/min, we can see that an AL19 (540L) pony cylinder is sufficient for a safe ascent from 30m/100′ depth. Do, however, consider that the psychological stress of dealing with a real out-of-gas emergency could substantially increase the diver’s SAC/RMV. It is worth considering using a larger cylinder as a contingency for diver stress in an emergency.

For more in-depth detail about pony cylinder gas management, see my comprehensive Pony Cylinder Guide.

Any diver considering doing training for wreck penetration diving should endeavor to develop robust fundamental diving skills and their ability for stress management. That training is usually only delivered on higher-quality training courses. You get what you pay for.

Improved fundamental diving skills will reduce your overall SAC rate, whilst developing stress management and resiliency will help prevent your SAC rate from becoming dangerously exaggerated when things eventually go wrong.

See my article How To Use Less Air When Scuba Diving

Exiting the wreck before the ascent

For wreck penetration diving, it is prudent to favor a larger pony cylinder because the extra volume may account for any unforeseen delays in exiting the wreck. Recreational-level qualified wreck divers are limited to 40m/130′ maximum linear distance from the surface. Their total wreck penetration distance is calculated by subtracting the bottom depth from 40m/130′.

For example, if they entered a wreck at 30m/100′ depth, they are consequently limited to 10m/30′ of penetration distance.

The time spent exiting the wreck must be incorporated into the bottom phase of gas calculations. When doing so, it is prudent to assume that the exiting speed will be 2-3x slower than the normal finning pace. This accounts for factors like silt-outs or minor entanglements.

In the table below, I have allocated 3 additional minutes at the bottom depth to allow for exiting a 10m linear distance out of the wreck.

Ascent Phase | Avg Depth | ATA | SAC | RMV | Time | Gas Vol Consumed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

4 min bottom | 30m | 4 | 30L/min | 120L/min | 4 min | 480L |

Ascent to safety stop | 17.5m | 2.75 | 30L/min | 82.5L/min | 2.5 min | 206L |

3 min safety stop | 5m | 1.5 | 30L/min | 45L/min | 3 min | 135L |

Ascent from stop | 2.5m | 1.25 | 30L/min | 38L/min | 1 min | 37.5L |

Total gas 859L | ||||||

(depth – stop depth) ÷2 + stop depth | (Depth÷10) +1 | Diver calculated | ATA x SAC | Time at Avg Depth | RMV x Time |

Using that example we can see that an AL19 (540L) pony cylinder is now insufficient for a safe exit of the wreck and ascent from 30m/100′ depth. An AL30 (860L) would be the absolute bare minimum sufficient size pony cylinder. Again, if we account for an increased SAC rate due to emergency stress, then it would be entirely prudent to consider an AL40 (1140L) as ideal.

See my article How To Use A Pony Cylinder

What are the advantages of pony cylinders?

Because the diver carries this pony cylinder with them, it is immediately available to them throughout their dive.

The diver is self-reliant and their survival does not depend upon the competency of their buddy. They have the physical and psychological security of knowing they can always reach the surface safely if they make a mistake in their gas monitoring or suffer a regulator failure.

While a scuba diver might endeavor to use less gas when scuba diving, there is always the risk of regulator failure or some other unforeseen event that will raise their air consumption rate or delay their bottom time before surfacing.

Experienced divers and instructors consider them highly advisable for wreck diving and also deep diving, which has a more significant risk. The best wreck diving courses will include tuition on how to use pony cylinders or other redundant gas sources.

See my comprehensive article explaining Deep Diving Risks

Pony cylinders at different levels of wreck diving

Wreck diving can be split into 3 broad levels of complexity and sophistication (Ref: Gary Gentile, ‘The Advanced Wreck Diving Handbook‘). Each level has very different demands in respect of training, knowledge, equipment and required experience. This is particularly true of the need for gas redundancy.

The typical ‘Wreck Specialty’ course for a recreational scuba diver falls somewhere between levels 1 and 2 – depending upon the course emphasis and the experience of the instructor providing the training.

Non-penetration wreck diving

Outside of the wreck diving. The gas management for these basic wreck dives is no different than any other open-water recreational dive. No specialist skills or equipment is required. Access to the surface is not impeded, so the full spectrum of Out-Of-Air (OOA) emergency protocols taught in recreational entry-level courses remain applicable.

These would include; Buddy Air Donation/Sharing (the primary OOA protocol), Controlled Emergency Swimming Ascent (CESA) and Buoyant Emergency Ascent.

Due to the availability of these emergency protocols, pony cylinders are not mandatory for non-penetration diving. They remain optional, based upon the individual divers’ preferences, as it would for any recreational dive.

Limited penetration wreck diving

Within the “light zone” diving. This definition matches the recommended maximum limitations that apply to recreational-level wreck divers.

The diver should never be more than 40m linear (horizontal + vertical) distance from the surface, beyond the illumination of external ambient light or in an area that prevents the side-by-side exit of two divers sharing air (no ‘restrictions’).

These recommended limitations, appropriate for the training given, theoretically enable the full spectrum of basic OOA protocols to remain available to the diver.

However, the increased risk of disorientation, silting and entanglement within a wreck can lead to delays exiting a wreck or prevent air-sharing protocols from being practicable. These factors make the use of a redundant air source much more advisable and most agencies recommend their use for these activities.

The size/capacity of pony cylinders should reflect the overall gas management plan and, as a general rule of thumb, should be no less than 1/3rd of the divers’ primary gas capacity. Divers should adopt the ‘Rule of Thirds’ for wreck penetration (1/3rd In – 1/3rd Out – 1/3rd Reserve) and retain the redundant air source as a further 1/3rd redundant reserve.

See my article Top-10 Tips For Wreck Penetration Safety

Full penetration wreck diving

Beyond the “light zone” wreck diving. This definition exceeds the limits of recreational wreck diving and applies to technically qualified (Technical Wreck + Deco) divers who penetrate shipwrecks beyond the limits of ambient light penetration, through physical restrictions, and beyond a 40m linear distance to the surface.

Due to a much higher risk of disorientation, silt-out, entanglement, and entrapment, this level of diving demands much more redundancy and refined advanced wreck diving skills and protocols.

It is anticipated that basic OOA protocols would not be sufficiently effective or reliable. Whilst the Rule of Thirds gas management is adhered to, the duration (and often depth) of these dives demands a considerably larger gas capacity than pony cylinders can supply, which makes full double cylinders a mandatory minimum.

Air-sharing is still preserved as a contingency measure (requiring long-hose protocols for sharing through physical restrictions), but divers are also expected to apply gas management, via redundant air sources, to ensure that they can exit and surface the wreck without support.

The decision to use pony cylinders

Your individual decision to purchase/utilize a pony cylinder will really be dictated by the technicality of the wreck diving that you expect to be involved in. As a recreational diver, you are equipped with a spectrum of protocols that already prepare you for gas emergencies.

If you adhere to the agency’s recommended limitations on wreck penetration (and support these with an accurate risk assessment before and during the penetration), then you should remain confident that the basic OOA protocols will remain practicable. However, wreck penetrations can sometimes go wrong and equipping yourself with a suitably sized redundant air source is a good ‘insurance policy’ against unanticipated problems.

The purchase of pony cylinders should reflect a calculated requirement that supports your overall gas management plan as a contingency redundant reserve. If you don’t have a gas management plan, then you can’t intelligently calculate a redundant gas requirement.

Gas Management For Scuba Divers

The comprehensive, illustrated, metric guide to advanced gas planning and management for safer scuba diving. Only $9!

60 Pages. Printable PDF format. Fully Illustrated.

About The Author

Andy Davis is a RAID, PADI TecRec, ANDI, BSAC, and SSI-qualified independent technical diving instructor who specializes in teaching sidemount, trimix, and advanced wreck diving courses.

Currently residing in Subic Bay, Philippines; he has amassed more than 10,000 open-circuit and CCR dives over three decades of challenging diving across the globe.

Andy has published numerous diving magazine articles and designed advanced certification courses for several dive training agencies, He regularly tests and reviews new dive gear for scuba equipment manufacturers. Andy is currently writing a series of advanced diving books and creating a range of tech diving clothing and accessories.

Prior to becoming a professional technical diving educator in 2006, Andy was a commissioned officer in the Royal Air Force and has served in Iraq, Afghanistan, Belize, and Cyprus.

In 2023, Andy was named in the “Who’s Who of Sidemount” list by GUE InDepth Magazine.

Purchase my exclusive diving ebooks!

Originally posted 2018-03-07 23:55:31.

Hi Jonnie, I know personally of one fatality caused by a human error with a back-mounted pony. The diver didn’t distinguish between the pony reg and his primary reg. He mistakenly breathed the pony on the descent, swiftly ran out of gas and perished on the ascent. Obviously, that was a contributing and initiating factor; the inability to effect appropriate self-rescue and/or stress management is what prevented an eminently survivable issue from becoming an accident. Equipment without the associated skillset doesn’t mitigate risks. Other than that fatality, I’ve heard numerous accounts of near-misses and avoidable incidents occurring because of skill deficit and/or unideal application of pony cylinders.

As a solo diver, I usually dive with my 3L pony, which allows me complete peace of mind in the event of a valve, first, or second stage failure at depth. I can always make a controlled assent and safety stop from any recreational depth. As for carrying it, I’ve had the local wetsuit shop make me a tank sleave from 2mm Neoprene with double 2″ cam-band loops to attach to my main scuba cylinder…cost $15. I’m a little confused as to a con of back carry being hose/SPG confusion? As for the SPGs, for most divers, the primary is always going to be mounted on the left side and with a pony, it’s SPG is routed on the right (pony is back mounted on the right). There can’t be any confusion. As for the octopus second, I’ve removed it from the primary first stage and placed it on the pony regulator, which is rounded down right side as normal. Again, no confusion issues.