Technical Diving Experience: The Complacency Paradox

It is easy to assume that acquiring greater technical diving experience must increase safety. This is a flawed assumption. Accident statistics in technical diving, along with other sporting and industrial fields, show a distinct tendency for elevating risk as significant experience accumulates. The reason is the insidious creep of complacency.

How can complacency increase with technical diving experience?

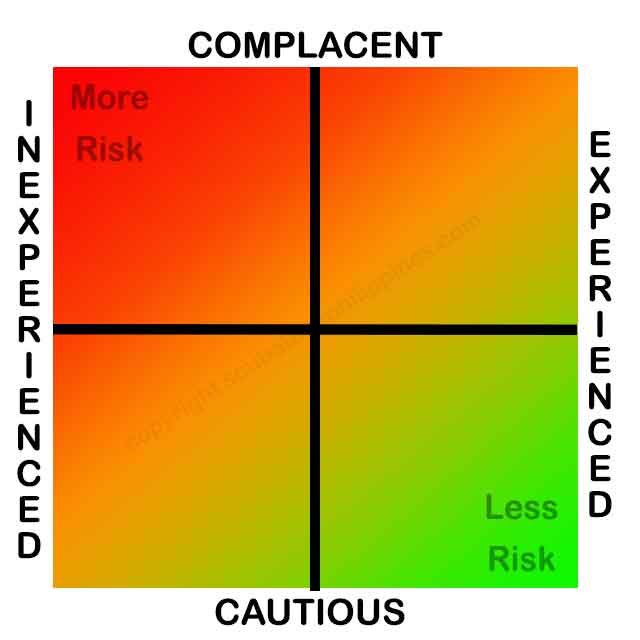

I would suggest that there are three relationships between technical diving experience and complacency:

- A complacent-inexperienced diver is a tragic accident waiting to happen.

- A complacent-experienced diver is comparably risk-prone to a cautious-inexperienced diver.

- A cautious-experienced diver is well insulated from risk.

Technical diving experience: Complacent-Novice diver

Needless to say, the biggest risk group for accidents is divers without significant experience, but who possess a high degree of confidence or complacency. This does happen… and has been studied.

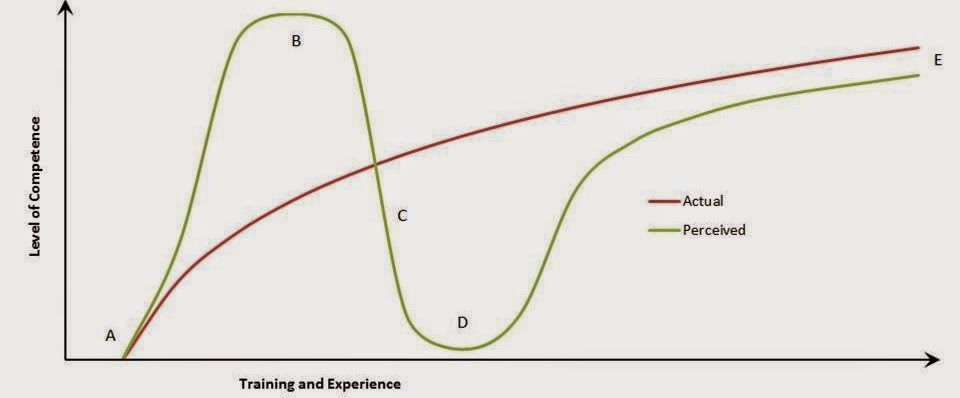

It is known as the Dunning-Kruger effect. That term, originating from a psychological study at Cornell University in 1999, describes how relative experience plays an important role in an individual’s self-perceptions of capability. In short, it describes how divers of relatively low ability might perceive themselves as far more capable than they actually are. It occurs when those individuals do not yet have the ability or knowledge to accurately evaluate their competency.

You don’t know what you don’t know

In short, you don’t know what you don’t know – and when you’re a novice technical diver you don’t know very much. Being unaware of the dangers, coupled with over-confidence in your abilities, can lead to very flawed decision-making and significant risk.

Acquiring more experience tends to resolve that inability to perceive relative weaknesses and capability deficiencies. In technical diving, this may include exposure to situations in which the diver fails to perform as they previously expected. A ‘wake up’ call occurs. Sometimes that failure is lethal, so “learning from your mistakes” on actual technical dives is never a recommended approach.

Until the time experience overcomes flawed self-perception, divers can only be cautioned to dive conservatively. When novice technical divers adhere to prudent and conservative dive practices, they are relatively well insulated from risk.

Technical diving experience: Cautious-Novice diver

This describes a technical diver of relatively minor experience who understands their limitations and applies prudence and appropriate conservatism to their tech diving activities. Whilst their inexperience means they are less capable of handling emergencies, they have restricted the parameters of their diving so that mishandled emergencies do not have catastrophic medical consequences. They keep diving more forgiving of error.

In addition, these divers lessen their risk of human factors attributing towards emergencies by moderating the challenge of the dives undertaken to ensure that the inherent task loading and skill requisites are comfortably within their capability range.

Technical diving experience: Complacent-Experienced diver

Beyond over-confident novice divers, I feel that one of the biggest dangers facing modern technical divers is a barrage of influences that seek to distort perceptions of what ‘experienced’ actually means.

Formal training is typically our first acquisition of experience at a given level of diving. However, deliberate practice training is supervised, staged, and controlled. It is artificial in many ways. Real diving is not. No matter how diligent the instructor, or how prestigious the initials of your technical training agency are, a certification course cannot provide you with the harsh lessons that you will eventually encounter as an active technical diver.

Training is inherently psychologically safe

No matter how realistic or challenging a technical diving instructor makes their training, I’ve yet to meet an instructor who’d actually let students perish in training. A supervisory safety net always exists; this is understood by the student. It detracts enormously from the psychological impact of simulated scenarios. There are also some incidents that couldn’t ever be safely simulated. The real learning only starts after the course ends.

Acknowledging that ‘the real learning’ starts after qualification, we are then told that our accumulation of logged dives shows our experience level. That’s a half-truth.

Quality versus quantity of experience

What matters isn’t the number of dives, but rather what we learned on those dives. Non-eventful and benign dives are relatively valueless in developing experience beyond improving basic equipment and procedural familiarity.

The more we dive, the more chance we have to encounter ‘Mr. Murphy’ and actually learn something new. However, these are random events and, hopefully, the most serious ones are very rare.

As an example, I dived for over 25 years and never suffered an SPG failure. In the 2 months prior to writing this article I’ve had 3 consecutive SPG failures; one explosive rupture, one stuck needle that didn’t drop and one needle that didn’t rise. Now I know all about SPG failures in reality.

As the years have passed, I’ve experienced all manner of technical diving emergencies; equipment failures, human factors, environmental factors and even severe marine-life injuries. I’ve managed to deal with them effectively (or else I wouldn’t be here now). It’s taught me that I can deal with many issues. However, within those lessons exists the seeds of arrogance and complacency.

Experience can make you a worse diver

Experience can be a bad thing. It can amplify bad habits and make you a worse diver over time.

This is why training must focus on perfection. Bad habits cannot persist after training, or else they can become indelibly ingrained through repeated use – and the perception that ‘it worked so far’, so it must be suitable. Most importantly, acquiring significant experience can lead to complacency.

Complacency kills divers. It kills pilots, soldiers, motorists, construction workers, electricians, astronauts, extreme sports athletes, and it kills lion tamers.

If a situation has the opportunity to kill you, then your only safeguards are the diligent application of the correct skills, procedures, and equipment to mitigate those risks; otherwise, leave that environment.

Every instance of survival and success in a potentially lethal environment conditions us to become more comfortable venturing there. As we get comfortable, we are tempted to slack off. As we slack off, we see – for a while – that slacking off was fine.

Normalization of deviance

This psychological pitfall is known as the ‘Normalization of Deviance’.

We get complacent because we ‘get away’ with deviating from a proper procedure or protocol once. That can justify repeating the deviation again. Each repetition further reinforces that the deviation is appropriate. At that point, the deviation becomes the new norm. Once the new norm is established, we may be tempted to deviate again from that.

The process repeats and the deviation from our original, proven, and prudent approach can become more and more severe. Eventually, events conspire to test our procedures or protocols. At that time, we realize we have deviated so far from the proper way of doing things – we experience failure.

Accumulation of experience is all too frequently used as the justification to deviate from the normal and correct approach.

Normalization of deviance accounts for many human factors incidents, where people who should know better suffer catastrophe because they simply failed to apply the critical procedures that they knew should be applied.

Technical diving experience: Cautious-Experienced diver

It’d be comforting to think that eliminating complacency was a natural end-point in technical diver development. That it was a stage of expertise that we reach once we’ve learned enough lessons along the way. It is not.

Being a cautious-experienced diver is an unstable state of existence.

Many technical divers experience temporary periods of being a cautious-experienced diver. This often occurs as a result of a near-miss emergency or peer tragedy. An incident occurs that serves to remind the diver of their shortcomings. A wake-up call happens.

Technical diving wake-up calls

For a time post-incident, the diver is motivated towards a more cautious approach. They might tighten their adherence to proper protocols, engage in refresher skills training, perform more diligent equipment maintenance or reduce the severity of their diving activities.

As time passes and further successful dives are made, the mechanisms that cause complacency relentlessly conspire to evaporate that sense of caution. Warnings are forgotten or, again, justifications can be made.

Surviving technical diving in the long-term demands a keen aversion to risk. That aversion drives us to mitigate and minimize risks. Complacency is that insidious whisper from our ego that the risks no longer apply to us; by virtue of our experience.

Learn lessons from survivable mistakes

As mentioned previously, I’ve learned many lessons from my technical diving experience. The successes taught me what I can achieve. They were not the most important lessons I learned.

My failures taught me the most. So did the failures of my peers in the technical diving community. From those failures, I’ve learned about my thresholds. That enabled deliberate training to improve my performance.

I’ve learned that things invariably and eventually DO go wrong, regardless of your skill, knowledge, diligence, and assiduous preparation. Understanding this simple fact helped promote a mental safeguard against complacency. It is a case of when, not if, something goes wrong – and if I am found lacking or unready on that next occasion then I might not survive.

Complacency creeps into your diving

I’ve caught complacency creeping into my mindset on a myriad of occasions. It seems compelling. As a result, I am very cautious about becoming complacent now. I analyze every dive I undertake and one factor that I always consider is whether I displayed complacency, major or minor, in any aspect of the dive.

Being aware of the dangers of complacency helps overcome those justifications that lead to complacent behavior.

Look for complacency on the easy dives

When I find evidence of complacency, it’s usually on dives where I feel the dive parameters are well within my skills, knowledge, and experience:

- Dives that I’ve conducted numerous times before; like the routine technical course dives that I conduct nearly every week.

- No-stop or limited deco dives after a series of deeper mixed gas dives.

- Open-water tech dives following a period of demanding technical wreck penetration dives.

- Open circuit diving following a spate of CCR diving.

What types of complacency affect divers?

From my observations as a technical diving instructor over the years, I have learned to recognize complacency in three distinct forms: routine, adaptation, or peer influence.

Routine complacency

Routine complacency is relatively self-explanatory. If you’ve done the same thing enough times it can lead to a temptation for short-cutting the correct procedures. The technical diver attains a high level of comfort through routine diving and that comfort, in turn, diminishes their perception of risk; empowering the justification of improper or abbreviated procedures.

“I’ve done 500 dives and I know my equipment like the back of my hand. There really is no need to complete a full pre-dive equipment check”.

Adaptive complacency

Adaptive complacency is less understood. The best illustration comes from driving a vehicle. If you drive on the highway for hours at high speeds and then turn off onto a slow-speed road, it feels as if you are literally crawling along. In driving psychology, this is known as “speed adaptation”. When it occurs, the motorist cannot rely on their sensation to gauge the appropriate speed.

For technical divers, complacency can also arise through adaptation to high-demand diving, followed by a swift return to less demanding dives. The tech diver can no longer rely on their experience to gauge appropriate risk. Their immediate experience recognizes the reduction of risk and leads to a perception that there now exists little or no risk.

“After a fortnight conducting exploratory 6-8 hour mixed-gas CCR cave dives, today’s 40-minute dip to my favorite wreck at 180 feet is child’s play and needs no special attention”.

Contagious complacency

A contagious complacency is a form of peer influence where one member of a group exhibits complacency which then transfers to the rest of the group. When this happens, an entire diving team can sink into arrogant over-confidence that can lead to unanimous support for justifications to deviate from safe protocols.

“As a regular dive team, we have over 80 years of combined tech diving experience between us. The ‘rule book’ wasn’t meant for divers like us. Who can object when 80 years of experience agrees that this protocol is unnecessary”.

Technical diving experience and overcoming complacency

The routine dives, the supposedly benign dives, and that foot-off-the-throttle diving serves to lull us away from the state of healthy wariness that keeps us sharp and safe. It is those dives that make us feel justified in relaxing our guard and abandoning known best practices. When we feel that compulsion to relax, we must recognize it as a trigger to exert self-discipline and greater caution. That may feel counter-intuitive, but it is very prudent.

Complacency is inevitable. Accept that.

We can best guard against complacency by making a commitment to diligently, and without exception, adhere to best practices and protocols. On occasions, our experience might present us with, seemingly justifiable, reasons for amending those best practices and procedures. Diving techniques and approaches do develop, after all.

If you want to deviate from accepted best practices, treat it as a formal change process. Do not make such decisions on a whim. What I suggest is that an external second opinion is always sought when formally adapting and amending accepted best practices. Seek a Devil’s advocate, if necessary.

Conduct frequent self-audits of your mindset

Consider doing routine ‘audits’ of your practices and procedures. Audit your own diving practices frequently and honestly; with respect to what you were taught and previously accepted as the correct methods. Get an external audit occasionally – a new training course, refresher, or expert evaluation. You may not feel like you need them, but that’s the very reason why you do need them.

Do respect the ‘experience paradox’. As you acquire more experience and skill you become more prone to complacency. Complacency kills the best of us.

Have you ever had a wake-up call about complacency when diving? Share your story in the comments section below.

About The Author

Andy Davis is a RAID, PADI TecRec, ANDI, BSAC, and SSI-qualified independent technical diving instructor who specializes in teaching sidemount, trimix, and advanced wreck diving courses.

Currently residing in Subic Bay, Philippines; he has amassed more than 10,000 open-circuit and CCR dives over three decades of challenging diving across the globe.

Andy has published numerous diving magazine articles and designed advanced certification courses for several dive training agencies, He regularly tests and reviews new dive gear for scuba equipment manufacturers. Andy is currently writing a series of advanced diving books and creating a range of tech diving clothing and accessories.

Prior to becoming a professional technical diving educator in 2006, Andy was a commissioned officer in the Royal Air Force and has served in Iraq, Afghanistan, Belize, and Cyprus.

In 2023, Andy was named in the “Who’s Who of Sidemount” list by GUE InDepth Magazine.

Purchase my exclusive diving ebooks!

Originally posted 2018-03-07 23:57:16.