Risk Assessment in Scuba Diving: The Key Steps To Safer Dives

As one of the most exhilarating adventure sports, scuba diving offers an unmatched experience of exploring the underwater world. However, with the excitement comes a certain level of risk that divers must be aware of and prepared for. This is where risk assessment in scuba diving becomes critical.

Understanding scuba diving risks, dive accident statistics, and assessing your own diving proficiency are all important steps to take before diving into the deep. Panic is also a major factor that can contribute to accidents, and knowing how to handle it is key.

In this article, I will take a deep dive into the key steps involved in risk assessment in scuba diving. You will learn the factors contributing to diving accidents and the five-step process for assessing and mitigating potential risks.

Additionally, I will discuss the fail-safe principle and risk acceptance, which are crucial concepts for any diver to understand. By the end of this article, you’ll have a solid understanding of how to conduct a thorough risk assessment and take the necessary steps to ensure safer dives. So, let’s get started!

Understanding the Risks of Scuba Diving

Scuba diving is an exciting and adventurous activity, but it also has inherent risks that need to be acknowledged and managed to ensure the safety of divers. According to published statistics, the risk of dying from scuba diving activities is calculated at 1 in every 200,000 dives.

That equates to rates of:

16.4 annual deaths per 100,000 divers: DAN (USA)

14.4 annual deaths per 100,000 divers: BSAC (UK)

Those statistics are based on the number of certified divers and an assumption that every diver conducts an average of 5 dives per year.

For comparison, the fatality rate for motor vehicle accidents in the USA is approximately 16:100,000 motorists. You will understand that the risk is not averaged to be equal for everyone. Rather, it is higher or lower based on the individual motorist’s experience and attitude toward driving safely.

That is also true of scuba divers. Your statistical risk of an accident is drastically higher if you:

- Are poorly trained

- Do not routinely practice skills

- Are inexperienced

- Dive beyond your ability

- Do not apply risk management

- Disregard safe diving practices

- Conduct more dangerous dives

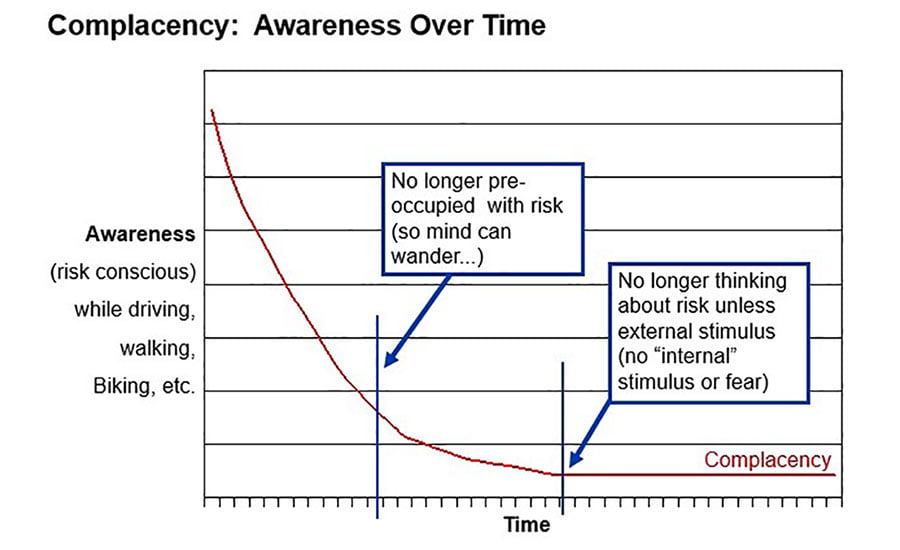

- Allow complacency to occur

- Use inappropriate or inadequate gear

All diving accident statistics in this article are quoted from ‘Diving Medicine for Scuba Divers‘ by Carl Edmonds.

They include a combination of accident study results from DAN, BSAC and other organizations.

Common risks of scuba diving

Despite the rigorous training and safety measures that are put in place, scuba diving still involves numerous risks that can lead to accidents. These risks include:

- Decompression sickness

- Lung overexpansion injuries

- Drowning

- Marine life injuries

- Equipment failures

Moreover, due to the underwater environment and the equipment used, these risks can be exacerbated in case of emergencies.

Avoidable dive-related injuries and fatalities

Several factors routinely contribute to diving accidents. For example, the following statistics illustrate some of the most common avoidable causes of scuba diving deaths:

- Running out of gas: 41%

- Equipment failures: 35%

- Regulator failure: 14%

- BCD failure: 8%

- Inappropriate gear or misuse: 35%

- Fins: 13%

- BCDs: 6%

In the majority of these incidents, flawed judgment has occurred. This emphasizes the need for improving risk assessments.

Additionally, impaired situational awareness and inadequate contingency skills will have played a role in the accidents occurring or continuing.

Both are factors that could be addressed by:

- More effective dive training

- The use of deliberate practice to preserve skills

Skill proficiency and diving accidents

Low skill proficiency and the inability to apply fundamental scuba training also contribute to diving accidents.

The following statistics highlight the training and skill proficiency-related problems that lead to diving accidents:

- 90% failed to release their weight belt

- 50% failed to inflate their BCD

- 50% died after reaching the surface

- 50% encountered buoyancy control problems

- 40% were grossly over-weighted

- 39% involved a panicked diver

- 25% got into difficulty at the surface

- 10% were uncertified for the activity conducted

- 4% resulted from failed air-sharing ascents

- 1% of divers died while attempting a rescue

Divers with higher levels of diving skill proficiency would have been better able to handle these issues or avoid them entirely.

Diving comfort zone and over-confidence

As such, it can be suggested that these divers must have been diving above their comfort level.

- Divers confuse confidence level with comfort level.

- Comfort level describes objective competency, not a subjective opinion

- Comfort zone has to include dealing with the worst-case scenarios that could arise

- An uneventful, undemanding dive is not evidence of being inside one’s comfort zone

Diver over-confidence is a well-known issue. It can result from:

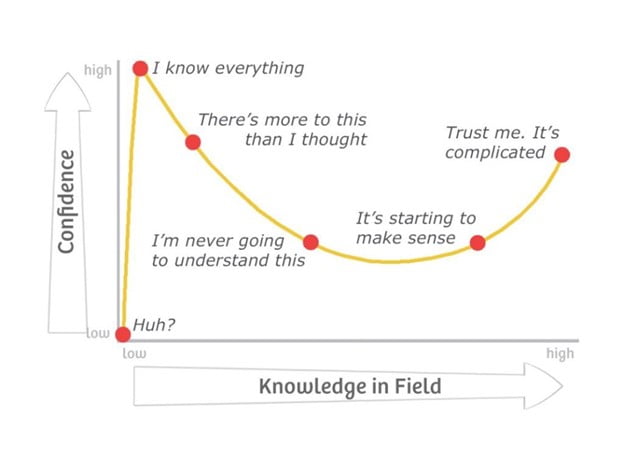

- Dunning-Kruger effect in beginner divers

- Complacency among experienced divers

It is important to note that divers only recover from the Dunning-Kruger peak of over-confidence if they have enough self-awareness to reevaluate their ability as experience grows.

A deficit in self-awareness can mean the diver remains over-confident indefinitely: at great risk to themselves.

Whilst the accumulation of experience can realign the diver’s level of confidence, it can also lead to increasing complacency. This is also dependent on self-awareness.

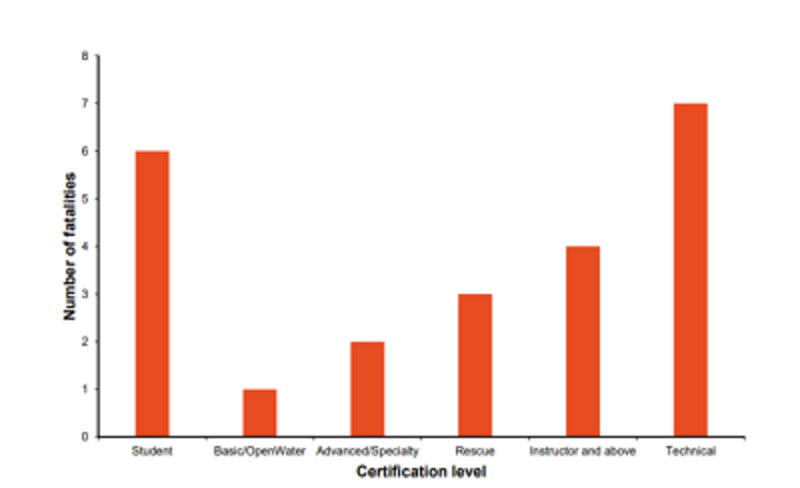

The development of complacency explains why fatal accident statistics decrease after entry-level, but then spike again when a moderate amount of experience is achieved.

It is important to remember that gaining more experience or further certifications does not necessarily increase your diving safety.

- Some of the most unsafe divers are highly experienced with low self-awareness

- Diving certifications don’t always represent skill proficiency

- Training courses can be inadequate

- Some dive instructors certify incompetent divers

- Your ability when certified may not be your ability today

- A certification card in your wallet or purse doesn’t save your life

Skill fade and self-assessing dive ability

Consequently, it is important to recognize that the ability to accurately self-assess competence relative to the dive being performed is critical. However, that ability is often compromised by heuristics and cognitive biases.

In addition, the self-analysis component of risk assessment is often compromised by not recognizing skill fade. Divers tend to simplistically base their self-analysis on the certification cards they possess. In doing so, they neglect to consider the actual skillset that certifications represent.

That is especially relevant to emergency skills. As an example, ask yourself when was the last time you practiced air-sharing ascents, regulator free-flow breathing, or BCD oral inflation for buoyancy control.

Many divers will not have practiced those skills since their initial Open Water course. Yet, they will perform risk assessment for their diving with the presumption that those skills will always be available and reliable.

Over-confidence and panic

Panic impedes effective judgment and skill performance. A major cause of panic is the sudden realization that an incident has spiraled beyond your control.

In essence, panic is often the psychological shock effect of complacency and over-confidence being shattered by cruel reality.

Over-estimating your ability doesn’t just get you into trouble, it crushes you mentally when things go wrong.

Divers with a higher level of self-awareness tend to be less prone to over-confidence. This trait tends to allow divers to learn more effective lessons from their experience. Indeed, a deficit in self-awareness is a leading component in the Dunning-Kruger effect.

Most lieutenants are lacking in self-awareness. In a 2020 study of new lieutenants and warrant officers fresh out of their basic course, there was a mismatch between the officers’ self-reported level of competence and the level of competence reported by more senior leaders who worked with them.

West Point Lieutenants Lack Self-Awareness, by Jordon Swain and James Watson

Likewise, divers who have undertaken challenging training courses that focused on realism have a more accurate idea of their true ability. Lastly, divers who receive effective critique from their instructors will develop an appropriate level of confidence.

Sadly, the dive training industry often focuses on falsely promoting diver confidence. This boosts diving course sales. Training avoids realism and honest constructive criticism is lacking. The emphasis of practice is on creating ease and comfort, rather than challenging the diver’s proficiency.

As a result, weak instruction compromises the diver’s ability to perform an accurate risk assessment. It could be suggested that this plays a major role in diving fatalities.

Diving conditions and diving accidents

The diving conditions and dive plan also have a bearing on accident statistics.

- 36% of fatalities involved difficult water conditions

- 12% of deaths involved excessive depth relative to the diver’s training and experience

Both of these factors should be covered by risk assessment as input into dive planning.

Factors that contribute to diving accidents

Several factors contribute to diving accidents, and the following statistics highlight some of the most common factors:

- 86% were separated from their buddy or diving solo

- 50% of these deaths were associated with experienced divers (> 20 logged dives)

Risk assessments can help avoid the accidents described by all of the statistics mentioned above. By carefully evaluating the potential risks of a dive, divers can take steps to avoid or mitigate those risks.

The importance of risk assessment in scuba diving

A risk assessment is a process that helps identify and analyze potential hazards and the associated risks involved in a particular activity. In the context of scuba diving, a risk assessment involves evaluating factors such as the environment, equipment, and the divers themselves to identify and mitigate potential risks that may arise during a dive.

Benefits of conducting a risk assessment

Conducting a risk assessment before a scuba diving expedition has several benefits, including:

- Identifying risk potential: A risk assessment can help identify potential hazards and risks, thereby minimizing the likelihood of accidents.

- Understanding risk severity: The process ensures that divers do not wrongly discount risks or become complacent about them.

- Enabling effective mitigation: By identifying potential risks and hazards, a risk assessment can help divers find solutions to the problems that are identified.

- Increased situational awareness: A risk assessment can increase situational awareness when hazards are consciously considered prior to diving.

Overview of the risk assessment process

The risk assessment process in scuba diving involves several steps, including:

- Identifying hazards: The first step is to identify potential hazards that may arise during the dive. These may include environmental factors such as weather, currents, and marine life, as well as equipment-related risks and human factors such as diver experience and medical conditions.

- Assessing the risks: Once the hazards have been identified, the next step is to assess the associated risks. This involves evaluating the likelihood of a hazard occurring and the severity of consequences if it does.

- Managing the risks: The final step is to manage the risks identified during the assessment. This may involve implementing measures to mitigate the risks, such as using appropriate equipment, modifying dive plans, or even aborting the dive before it starts.

By identifying potential hazards and risks and taking appropriate measures to manage them, divers can ensure that they can enjoy the underwater world safely.

The scuba diving risk assessment process

The risk assessment process in scuba diving typically involves five key steps:

- Identifying potential risk

- Assessing the severity of each risk

- Determining the likelihood of risk occurrence

- Grading the risks

- Modifying grade by risk mitigation

Here’s an overview of each step:

1. Identifying potential risks

Divers should carefully evaluate the dive site, dive plan, environmental conditions, and equipment used to identify any potential hazards that may pose a risk during the dive. This can include factors such as:

- Depth: narcosis, gas consumption, gas density

- Visibility: silt, topography, darkness

- Currents and surge

- Access to the surface: direct, delayed

- Ascent requirements: stops, ascent rate

- Hazardous marine life

- Weather conditions: waves, rain

- Anticipated exertion level

- Breathing gasses: O2 toxicity, CO2 retention

- Equipment suitability

- Dive gear serviceability

- Life-support system redundancy

- Familiarity with the dive demands

- Diver physical and psychological fitness

- Predisposition to dive ailments: DCS, O2 toxicity

Understanding risk factors is an outcome of dive knowledge and experience.

A poorly taught diver will struggle with performing effective risk assessment because they are unaware of applicable risks, or the factors that may provoke them.

Likewise, gaining diving experience is irrelevant unless the diver has been analytical and contemplative to learn lessons from each experience.

If you want to perform effective risk assessment in scuba diving, you must invest time and effort in learning about diving risks.

2. Assessing the severity of each risk

Once potential hazards are identified, divers should assess the severity of each hazard by considering the potential consequences or harm that may result from its occurrence.

In essence, judge whether a risk can potentially cause:

- Death

- Severe injury

- Major injury

- Minor injury

- Trivial injury

Risks in isolation versus the accident spiral

When performing this step it is important to realize that hazards often contribute to an accident spiral.

For instance, the hazard of a regulator free flow might be discounted because the diver once learned a protocol for dealing with it. However, when diver stress and task loading are accounted for, the diver may lose control of their buoyancy or lose contact with their buddy. In turn, this leads to further hazards and greater severity.

Do not assume that hazards occur in isolation. They frequently have a cause-effect relationship with other hazards.

Risk severity from a predictable accident chain

When assessing risk severity, consider how risk may contribute to a chain of issues. The severity that matters is the outcome at the end of an accident chain.

For example, an uncontrolled ascent from a shallow dive may be considered low in severity (DCS risk). However, in an area of heavy boat traffic, the risk may be very severe (propeller strike).

Alternatively, the risk of a flooded mask may be considered low in severity. By itself, it causes no physical injury. However, if the diver had weak stress management, they might panic and shoot to the surface.

The risk severity then becomes DCS. Statistics also show that panicked divers often fail to gain buoyancy at the surface and drown. I know of at least one real-life example where a diver perished as a result of a flooded mask accident chain.

The important takeaway is that risk severity has to be individual to the diver. For that reason, understanding risk severity demands self-awareness and self-honesty.

Consider risk severity with realism, not idealism

For that reason, the perceived severity of a regulator free flow would have to be moderated by the diver’s skill-specific proficiency and stress management capacity.

This is why expert divers learn to plan their dives based on worst-case scenarios. In contrast, inexperienced divers tend to assume that real-life emergencies can be dealt with just as easily as they experienced during undemanding, unrealistic training.

3. Determining the likelihood of risk occurrence

Divers should assess the likelihood or probability of each hazard occurring based on various factors such as:

- Historical, statistics, and local data

- Water conditions

- Dive parameters

- Equipment suitability

- Equipment reliability

- Diver skill proficiency

- Activity specific experience

- Specificity of training

- Diver stress management

This can help prioritize risks and focus on higher likelihood hazards that may pose a greater threat.

One common failing that undermines risk assessment is that divers simply assume that risks don’t apply to them. Risk assessment is often avoided entirely because of the presumption “it won’t happen to me“.

The reality, I am sad to say, is that emergencies are a matter of ‘when‘, not ‘if‘. Every dive is a roll of the dice. The reality is that eventually, something will go wrong. Surviving that event is dependent on effective preparation. In turn, that requires accepting the likelihood of emergencies occurring.

4. Grading the identified risks

Having identified risks and categorized them by severity and likelihood, you should now grade them.

Grading risks helps to prevent them from being discounted. For instance, it is common to disregard infrequent risks, even if they have very severe consequences. Likewise, it is normal to discount risks with low severity, even when they happen frequently.

The table below gives an example of numerical risk potential grading. In turn, that grading should reflect your risk prioritization and the risk mitigation you need to apply.

Risk potential assessment matrix

Severity – Likelihood | | Fatal (5) | Severe Injury (4) | Moderate Injury (3) | Minor Injury (2) | Trivial Injury (1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Very common (5) | 10 | 9 | 8 | 7 | 6 |

Frequent (4) | 9 | 8 | 7 | 6 | 5 |

Occasional (3) | 8 | 7 | 6 | 5 | 4 |

Rare (2) | 7 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 3 |

Very Rare (1) | 6 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 |

It is important to note that these are unmodified risk potential grades of risk. As a scuba diver, you now have the opportunity to modify those risks.

When doing so, you can:

- Reduce the likelihood of the risk

- Reduce the potential severity of the risk

- Attempt to do both

5. Modifying risk potential grade by risk mitigation

Based on the severity and likelihood of identified hazards, divers should establish appropriate risk control measures to mitigate or avoid the risks. This can include:

- Implementing procedures and protocols

- Amending the dive plan

- Using more appropriate dive gear

- Utilizing equipment redundancy

- Creating contingency plans

- Having an emergency response plan

- Developing specific risk-related skillsets

- Improving stress management and resiliency

Fail-safe diving risk mitigation

A fail-safe is a solution that, in the event of a failure, inherently reduces the severity of consequences.

It is a principle applied in risk management that assumes emergencies will occur and, nonetheless, ensures that they do not have catastrophic outcomes.

One example of fail-safe in scuba diving is equipment redundancy. For instance, carrying a pony cylinder or using sidemount gear safeguards against the risk of a regulator failure. Failure can occur, but it is not a severe consequence.

Another example of fail-safe is emergency skills training. When a diver is genuinely proficient in rescue techniques they can prevent a diving emergency from becoming a fatal accident. This, in turn, may reflect in certain grades of risk being modified downwards.

Risk mitigation modifying the risk potential grade

In this final step of the risk assessment process, you should address every identified risk. Attempt to:

- Find fail-safe solutions that reduce the outcome severity of risks

- Find solutions that reduce the likelihood of risk occurrence

When those solutions are implemented, you should re-visit your risk potential assessment matrix. Re-grade the risks according to their modified level of severity and likelihood.

Is the risk mitigation acceptable?

The final decision on risk acceptance is individual. Divers have different tolerance levels of risk. What is important is that you base a risk acceptance judgment on an informed understanding of risk potential grade.

If you find that a risk potential grade is intolerable, you should not conduct the dive. The worst judgment is to shrug your shoulders and just hope for the best.

Alternatively, you may find the risk potential grade to be tolerable. As I’ve mentioned earlier, it is important to be self-aware when making that decision. Pride, bravado, peer pressure, and stubbornness should be ruled out.

Similarly, you should be content that the risk exposure is worth the rewards. High-risk dives should have some definable goal and valuable outcome.

Self-deception in risk acceptance

Scuba divers who have a high level of risk acceptance need to be realistic about their individual personality traits. It is enjoyable to flatter your ego by imagining yourself as an adventurer.

In reality, high-level diving explorers tend to have the following personality traits:

- High level of trait conscientiousness

- High level of openness to experience

As a result, elite divers tend to be:

- Risk-averse

- Diligent

- High attention to detail

- Patient

- Conservative

- Rational

- Calculating

- Plan orientated

- Self-restrained

- Self-aware

- Circumspective

- Cautious

- Curious

- Hungry for knowledge

- Self-critical

- Open to critique

- Eager for opinions

- Acceptable to changes

Challenge your self-awareness. If you are considering conducting high-risk dives due to a sense of adventure, how closely do you match the characteristics of the dive adventurers who survive and thrive under risk?

Start applying risk assessment in scuba diving

Risk assessment in scuba diving is an essential aspect of any dive plan. By taking the time to understand the risks, assessing your own abilities, and following the five-step process for risk assessment, you can minimize the potential for accidents and ensure safer dives.

Factors contributing to diving accidents can be numerous, but with proper risk assessment and mitigation strategies, divers can minimize their exposure to danger. Grading potential risks in severity and likelihood, as well as understanding the fail-safe principle and risk acceptance, are important concepts to keep in mind.

Ultimately, the key to safe scuba diving is preparation and awareness. By understanding and applying the principles of risk assessment, divers can have the confidence to explore the beauty of the underwater world while minimizing potential hazards. So, the next time you’re planning a dive, remember to conduct a thorough risk assessment and take the necessary steps to ensure a safe and enjoyable experience. Happy diving!

About The Author

Andy Davis is a RAID, PADI TecRec, ANDI, BSAC, and SSI-qualified independent technical diving instructor who specializes in teaching sidemount, trimix, and advanced wreck diving courses.

Currently residing in Subic Bay, Philippines; he has amassed more than 10,000 open-circuit and CCR dives over three decades of challenging diving across the globe.

Andy has published numerous diving magazine articles and designed advanced certification courses for several dive training agencies, He regularly tests and reviews new dive gear for scuba equipment manufacturers. Andy is currently writing a series of advanced diving books and creating a range of tech diving clothing and accessories.

Prior to becoming a professional technical diving educator in 2006, Andy was a commissioned officer in the Royal Air Force and has served in Iraq, Afghanistan, Belize, and Cyprus.

In 2023, Andy was named in the “Who’s Who of Sidemount” list by GUE InDepth Magazine.

Purchase my exclusive diving ebooks!

Originally posted 2023-04-19 00:44:12.

That would be a great aspect to expand upon. My plan is to cover weather and water conditions in greater detail as a stand-alone article. It’ll be linked from this article in due course.

Andy: I enjoyed reading your “Risk Assessment in Scuba Diving” Blog today. I fully agree with with what you have had to say. And as long time Instructor I try to build some of this discussion into my classes and on-site briefings. And where the last dive of the course is a student planned dive, I ask them to provide a site assessment and contingency plan as part of their presentation to me.

If you are in the practice of updating these blogs from time to time, as a Canadian diver, I wouldn’t mind seeing one small addition the the section on Identifying Potential Risks – Weather Conditions. Here I would add water temperature. For us this can be a year round consideration. And I am certain that you can understand why. It is something that we alway want to talk about in our dive plans here.

Thanks again for your good work.