The Changing Technical Diving Mindset: Issues in Modern Technical Diving

Technical diving went mainstream. It’s not a good thing in all respects. Are there issues in modern technical diving?

Having been actively involved in technical diving for over 2 decades as both a tech diver and trimix instructor, other divers sometimes ask me how things have changed since I first ‘went to the dark side‘.

There have been many changes; the equipment and technology used, the understanding of decompression and physiology science, the awareness of ‘tech’ amongst the recreational diving community, and, perhaps most strikingly, the demographics and attitudes of technical divers and the agencies that train them.

My Own Journey Into Technical Diving

When I first became involved in technical diving in the early 2000s, the technical diving community was very small. It was a tiny niche of very active and enormously experienced divers, who were rather insular and apart from mainstream sports diving.

I can’t remember ever seeing a technical diver during my first decade in diving. The internet was also in its infancy at that time, so unless you actually met and talked to a technical diver, you’d be unlikely to have any access to information. Regular bookstores didn’t stock specialist diving publications, and there was no Amazon, eBay, or blogs where you could stumble upon tech diving resources.

Technical divers were a rare breed

My first encounter with technical divers happened when I was training to become a divemaster in the UK just after the turn of the millennium. I was reasonably experienced at the time, having logged around 200 dives, and eagerly dove most weekends.

The conversations I had with those few divers over a series of weekends both inspired and motivated me. They graphically explained the hazards of the dives they did. They detailed the physical and mental capabilities, knowledge, and experience they’d needed to survive various incidents that had occurred to them. Compared to everything I knew about diving at that time, they seemed like men apart – pioneers and true adventurers.

I’ll admit that I was hooked from that moment on. With equal parts curiosity, trepidation, and ambition, I began researching more about extreme diving.

Technical diving resources were scarce

Resources were very scarce. There were books available, but I had to slowly source them through word-of-mouth alone. I placed orders in my local bookstore and had to patiently wait weeks before I could collect them. Over many months, I began filling a shelf with texts from divers like Bret Gilliam, Tom Mount, and Gary Gentile.

I digested those books, reading and re-reading them over and again, trying to make sense of the bewildering complexities they presented. I upgraded my diving equipment and started extending the limitations of the dives I undertook. It was a very haphazard affair and I made many mistakes along the way. But I slowly learned and I gained experience from those errors and close calls.

Recommended reading when preparing for technical diving courses

It was a couple of years, and a hundred more dives before I made the decision to actually embark on a technical diving course. I’d reached a stage where I had begun to feel confident that I was ready to progress into deeper, decompression diving. Tech instructors were still a rare commodity, but I managed to track down someone who could qualify me. His name was Mark Powell.

I contacted Mark and we arranged to conduct the first levels of tech training at an ice-cold quarry in Wales. I rushed out and bought what I felt was appropriate equipment. I went through the manuals and completed the necessary academic study. I felt I was ready and able.

That confidence was re-aligned within minutes of getting into the water with Mark. I was immediately overloaded. My buoyancy was horrendous. My equipment worked against me, causing unnecessary task loading and confusion. I lost situational awareness as soon as I had to perform any task. After that first weekend, I felt frustrated and humiliated. My prior confidence had been unfounded. I felt a strong temptation to quit.

Over several weekends of training, I just managed to scrape a bare pass. Mark was candid and honest about my need for improvement. I had an awful lot of practice to do and experience to gain before I should think about progressing any further.

Technical diving instructors were gatekeepers

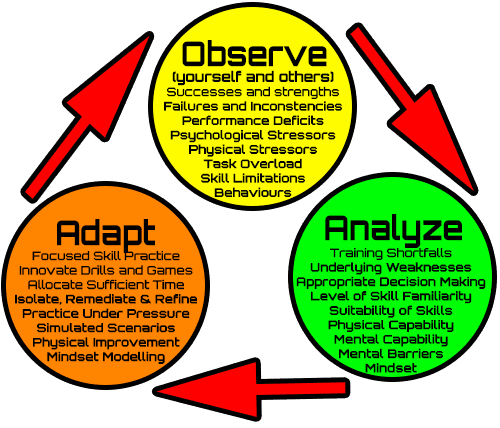

Mark had put me on the right route, but it was a long road ahead of me. However, I now knew my weaknesses and deficits, and most importantly, I had been instilled with a mindset that understood and strove for excellence.

Progress between technical diving certifications was slow

It was years before I took another tech class. During that time I was obsessed with correcting the deficits that I’d previously encountered. I practiced in the pool. I dove several weekends a month on the wrecks around the UK coastline, slowly making the equipment and protocols second nature. I networked within the small UK tech community, absorbing all of the information and perspectives that I could. I lurked silently on niche technical diving internet groups, observing the vehement debates and arguments that occurred there. I bought and studied newly released DVDs that illustrated Hogarthian and DIR diving approaches.

It was a long and contentious journey, throughout which I never lost sight of the lessons I’d originally learned on my first tech course. I knew I was fallible; and if my proficiency didn’t match the worst things that could happen on the dives I undertook, then I would seriously hurt myself, or worse.

Over the coming years, I did eventually progress my technical diving qualifications. As helium fills and trimix training become more accessible, I transitioned from (very) deep air to mixed gas diving. In 2007, I trained and became a technical diving instructor, but only allowed myself to work as an assistant for the first twelve months or so. I was cautious and patient, always aware of how much I didn’t know. For that reason, I patiently paced myself and invested my time in gaining the right levels of personal experience and capacity before taking on the sole responsibility for training new tech divers.

The State of Technical Diving Today

Contemporary technical diving has evolved enormously since my own first tentative experiences over a decade and a half ago. There have been many awesome improvements, but also there are new issues in technical diving now.

Mainstream agencies have adopted and promoted technical training to a much wider demographic of divers. Divers who, a mere decade ago, would have been considered as not having either the inclination, self-discipline, or motivation to evolve their physical and mental capability to the necessary levels of proficiency.

Issues in technical diving: Unrestrained monetization

Technical diving training seems to have become a cash cow; merely another corporate revenue stream to be exploited in the quest for bigger profits and happier investors.

The internet is now bursting with chat forums, groups, blogs, and video resources. Divers barely into recreational level qualification vociferously argue their perspectives on profoundly technical issues they’ve only ever read about online. Subject matter expertise, or even the slightest token of experience, no longer seems to be a common-sense prerequisite for voicing authoritative and unwavering opinions.

Issues in technical diving: Fast-track instructors

Technical diving instructors have gone from being a rarity to commonplace. They’re seemingly everywhere when it comes to offering courses, but nowhere to be found on the actual few tech explorations, projects, and boats. There are fast-track, guaranteed pass, qualification routes that routinely certify instructors to teach decompression, and even trimix, courses within a meager few dozen hours of actual experience.

Those rapidly promoted technical diving instructors, eager to recoup their financial investment, swiftly resort to incautiously hard-selling any and every diver onto tech training programs if they have only the barest prerequisites in qualification and experience. Actual diver proficiency, or motivation, ceases to become a factor for consideration.

These unprepared, inexperienced, and sub-proficient technical diving students still manage to pass technical training with alarming frequency. So logic demands that either modern technical diving training has become so miraculously effective and efficient that it compensates for even the most ill-prepared, incompetent student divers; or, as is most likely the case, that woefully inexperienced tech instructors are unable to apply the same high standards and diligence as used to be demanded.

What now concerns me greatly is that learning an appropriate technical diving mindset no longer seems to be the de-facto gateway into technical diving. Patience has been replaced with instant gratification. Risk-averse attitudes have diminished as divers gain technical certifications without ever really learning the bleak consequences of not being able to handle the dives they do.

Issues in technical diving: The lost gatekeeper mindset

Tech instructors cease to be ethical ‘gatekeepers’ acting in the student’s best interests and now function primarily as glib salesmen who pander to an instant-gratification diving culture, amongst which technical certifications are increasingly valued merely as prestigious trinkets.

Most importantly, and as a consequence, the technical diving certification seems to have lost its merit. Qualification can be gained so quickly and easily that it is no longer meaningful as a benchmark for proving the individuals’ capacity to safely undertake risk consequential dives, or even to understand what personal limitations they should be applying to their diving.

Issues in technical diving: Prioritizing convenience and ease

Getting technical diving qualified is now absurdly easy and, it seems, that simply having a plastic certification card in your wallet is often viewed as more than enough contingency against the worst that can happen.

The serious technical divers, as has always been the case, still seek ruthlessly honest tech training. They still exhibit patience, motivation, and humility. They still persevere when the going gets tough. They still strive for excellence.

What we, as a tech community, are losing is the ability to clearly differentiate the wheat from the chaff; to recognize the capable few from amongst the increasing pool of those brandishing identical level, but dangerously lower competency, qualifications.

The Challenges Facing Technical Diving

The biggest of the issues in technical diving I see in the contemporary tech community is that progression through technical diving qualification levels has accelerated immensely. I’ve explained why I think this happens, so now I must explain why I think the community is getting away with it.

More and more divers are getting tech qualified, but this hasn’t resulted in a catastrophic elevation in fatality statistics. I attribute this situation to three primary factors:

1. Technology Compensates for Proficiency

When I first started technical diving we planned dives on MS-DOS planning software that produced dive profiles unmoderated below the most aggressive baseline maximum values. First-generation technical diving computers were temperamental and expensive, consequently, very few technical divers used them. Helium supply, along with the training to use it, was rarely available in most locations; deep air dives to the absolute physiological limits were the norm for many technical divers.

As a result of these inherent demands, the aspirant tech diver had to compensate greatly through the slower acquisition of knowledge, skill, and experience. Technical dives would be limited by individual physiological thresholds that, in turn, had to be patiently explored and established.

The technical diver had to progressively learn their DCS thresholds and gain the requisite experience needed to arbitrarily tweak their own decompression curves. It was an era of “beer mat dive planning”, and successful refinement of your personal approach was entirely based on observing decompression stress and the ‘niggles’ when you returned back to the surface.

The same was true of narcosis, gas density, and CO2 management. Attaining thousands of dives experience and ingrained skills was the only means to compensate for degraded mental performance and carbon dioxide retention. Beyond that approach, divers could only progress through gradually incremental depths until they found the point beyond which they became a distinct liability. If you were too aggressive or incautious, the likelihood of surviving to learn from your mistakes was frighteningly low.

Contemporary aspirant technical divers are excused from that tentative approach. Nowadays, anyone can strap on a Shearwater, crank up Multideco, consult the web for optimal settings, and squirt enough helium into mixes to make physiological barriers irrelevant.

This is all fine – for as long as dives go exactly to plan.

Experience and competency shortcomings from rapid qualification timescales only expose themselves when catastrophe strikes. Only then does the diver discover if they’re woefully lacking the physical and mental capacity to keep themselves safe. It simply becomes a gamble, or a race, to actually acquire reliable worst-case scenario competency before an incident happens that the diver wouldn’t otherwise be able to deal with.

I liken it to a ‘fake-it-until-you-make-it’ situation. Rapid progression into very consequential depth ranges is empowered by fast-track qualification programs run by inexperienced technical diving instructors. Competency deficits in those courses are too frequently ignored by the instructor. That’s assuming the instructor is even actually aware of what the competency levels even need to be.

Encouraged and enabled by sales-hungry instructors, novice technical divers can easily develop a false sense of their true capability. Freed from the physiological and technological ‘speed bumps’ that used to exist, the diver is no longer forced into a patient and tentative approach to increasing their boundaries. It becomes far too easy to allow credit cards to empower qualification ambitions and then out-pace the development of baseline emergency survival capacity.

Put simply, a novice technical diver can nowadays skyrocket to the highest levels of technical diving qualification without any real internal or external barriers. This puts them unknowingly into a precarious position whereby the dives they are qualified to undertake are vastly beyond their reliable capacity.

When not if an incident occurs it becomes a lottery whether they’ll be able to deal with it and survive. They simply have to hope that such an incident doesn’t arise before their actual proficiency has caught up with their qualification progress.

2. Mainstream Agency Corporate Culture

I’ve observed the landscape of the technical diving community shifting drastically as the big recreational agencies have increasingly moved into the technical diving training market.

Corporate legal and financial board decisions seem to be the driving focus when they determine the necessary experience prerequisites, competency levels, and performance standards at technical instructor-trainer, instructor, and diver levels.

There has been a profound downward expectation shift on what is expected of a “technical diver”.

The justification for empowering increasingly fast-track progress through low-entry barrier tech qualifications may arise from accident statistics. Agencies typically quote rations of divers versus accidents. If that ratio doesn’t skew, then the training provision and certification standards may be deemed ‘adequate’.

However, massive inflation in the number of those getting technical diving certified will always tend to dilute the number of accidents – even when that number of accidents is rising. The ratio can actually be seen to shrink.

Allowing fast-track technical diving qualification, for financial gains, has opened the door for a recreational diving mindset to permeate into the technical community. Worse still, it’s empowered that same mindset to propagate upwardly to instructor and instructor-trainer levels.

People are now becoming technical ITs and instructors purely because it represents a financial lucrative investment. The aim is simply to flog as many courses as possible. There’s no underlying passion or motivation for actually technical diving.

The consequence of this dilution is that grossly inexperienced technical divers rapidly progressed into authoritative, role-model, technical instruction positions.

Needless to say, a novice technical diver that’s prematurely empowered to teach technical diving whilst still coasting high on the initial ‘Dunning-Kruger’ curve becomes a huge liability.

All that they are able to pass on to students is a flippancy of risks, an ignorance of consequences, and an overestimated valuation of proficiency.

This recreational agency modus-operandi of providing short, low-intensity, instructional courses to relatively inexperienced divers so that they can merely ‘deliver an agency product’ is deeply flawed in the technical diving context.

That approach creates and perpetuates entirely the wrong mindset. That same mindset expands quickly throughout the instructional ranks as profit-focused technical diving instructors are empowered to rush into ever-more influential teaching positions as quickly as their bank balances permit.

I think that system is probably beyond fixing. The only measures that’d resolve these issues in technical diving would entail the loss of profitability and an admission of error. Mainstream agencies simply don’t ever do these things.

3. A two-tier division of technical divers

What I predict for the future is an increasingly two-tier structure of technical diving.

Certain agencies will devalue the reputation of their technical certifications within the technical diving community. To such an extent that they won’t ever be accepted at face value.

This devaluation, in turn, will provoke the actually competent technical diving instructors within those agencies to switch to more credible tech certification agencies. That loss will further diminish those agencies by causing a drain of whatever experienced teaching talent they did have.

There’ll be many who carry technical diving certification cards, but few who’ll possess even the slightest competency and capacity to safely conduct the dives.

The emphasis will be entirely focused on individual dive operators and teams having to physically assess and confirm competency for technical diving, regardless of what qualifications customers possess.

I’d like to believe that when divers realize that c-cards alone are valueless it would cause a shift in demand – for more credible training. That, in turn, would affect agency profits and sales figures. Only then would profit-focused agencies start to re-evaluate their qualification practices.

Sadly, I don’t think that’ll happen. It won’t happen because those same agencies, those same dive centers, those same instructors, who are certifying sub-proficient tech divers will continue pandering and enabling their tech customer’s expectations, and take their clients onto technical dives with no further questions asked or resistance offered. They’ll do their utmost to keep themselves and their customers alive, but won’t ever say no to the money on offer.

For so long as the technical diving community tolerates and panders to incompetent tech divers, the problem will only flourish and grow. Transparency, honesty, expectation management, and the simple capacity to say “NO” has to take ethical precedence over the temptation to grab cash from incompetent divers and ignore, or compensate for, their shortcomings.

Naturally, this would be a painful experience for those who took advantage of unscrupulous, profit-hungry, instructors to fast-track their way into the tech community. There’d be many whose sense of credit-card-empowered entitlement and privilege would be offended by refusal, or merely being asked to prove their capacity.

In a world where demand dictates supply, it is ultimately the technical diving community itself that must endeavour to provide the right education and guidance to those considering taking the journey. Overcoming the issues in technical diving has to be solved by the technical divers themselves.

If you found this helpful, you’ll also love:

Recommended reading when preparing for technical diving courses

About The Author

Andy Davis is a RAID, PADI TecRec, ANDI, BSAC, and SSI-qualified independent technical diving instructor who specializes in teaching sidemount, trimix, and advanced wreck diving courses.

Currently residing in Subic Bay, Philippines; he has amassed more than 10,000 open-circuit and CCR dives over three decades of challenging diving across the globe.

Andy has published numerous diving magazine articles and designed advanced certification courses for several dive training agencies, He regularly tests and reviews new dive gear for scuba equipment manufacturers. Andy is currently writing a series of advanced diving books and creating a range of tech diving clothing and accessories.

Prior to becoming a professional technical diving educator in 2006, Andy was a commissioned officer in the Royal Air Force and has served in Iraq, Afghanistan, Belize, and Cyprus.

In 2023, Andy was named in the “Who’s Who of Sidemount” list by GUE InDepth Magazine.

Purchase my exclusive diving ebooks!

Originally posted 2019-02-04 17:20:27.